There are many stories born on Route 66 that tug at the heart, but perhaps one more than any other when, in June 1961, the lives of four little boys were changed forever.

James Dolphus (‘JD’) and Utha Marie Welch were a typical American couple in their early thirties. JD, a burly six-footer and 200lbs, was a truck driver for Trans-Con, while Utha was a housewife and stay at home mother for their four sons. Jimmy, 12; Billy, 9: Tommy, 8 and 5-year-old Johnny. (There had been another son, born between Jimmy and Billy, but Noble – named after Utha’s father – was a sickly child from birth and died in infancy.) This, however, didn’t stop both parents being involved in many local activities in their hometown of Spencer, Oklahoma.

Most of JD’s family lived in California and, in June 1961, the family set out from Oklahoma to drive to Tulare, California to see JD’s mother before she went in for surgery. Then they intended to return to Oklahoma via Colorado Springs. The boys were keen to camp during the trip and JD and Utha agreed they could take their Boy Scouts pup tent. On Thursday 8th June, a day into the trip, the family left Amarillo in the morning. It was late at night by the time they stopped for gas in Ash Fork, Arizona and enquired about a motel room. The owner would tell police that JD had thought the room too expensive and left. As the motel owner never spoke about the incident publicly (despite being the last person outside of the family and their murderer to see the Welches alive), one wonders whether, glancing at the family’s shiny two-year-old Oldsmobile – JD had only bought it two weeks earlier – and calculating the lateness of the hour and the small boys, quoted a price higher than normal.

No-one will ever know why the family didn’t then stop in Seligman where there were more motels. It may have been cost or it may have been that the boys were nagging their parents to camp. But eventually, around midnight, JD pulled into the side of the road around 13 miles west of Seligman. Even now, it’s a bleak and barren stretch of road, the plain of the Aubrey Valley stretching for miles around. The only cover were two large piles of rubble and it was beside one of these that JD pitched his sons’ tent while he and his wife slept in the Oldsmobile.

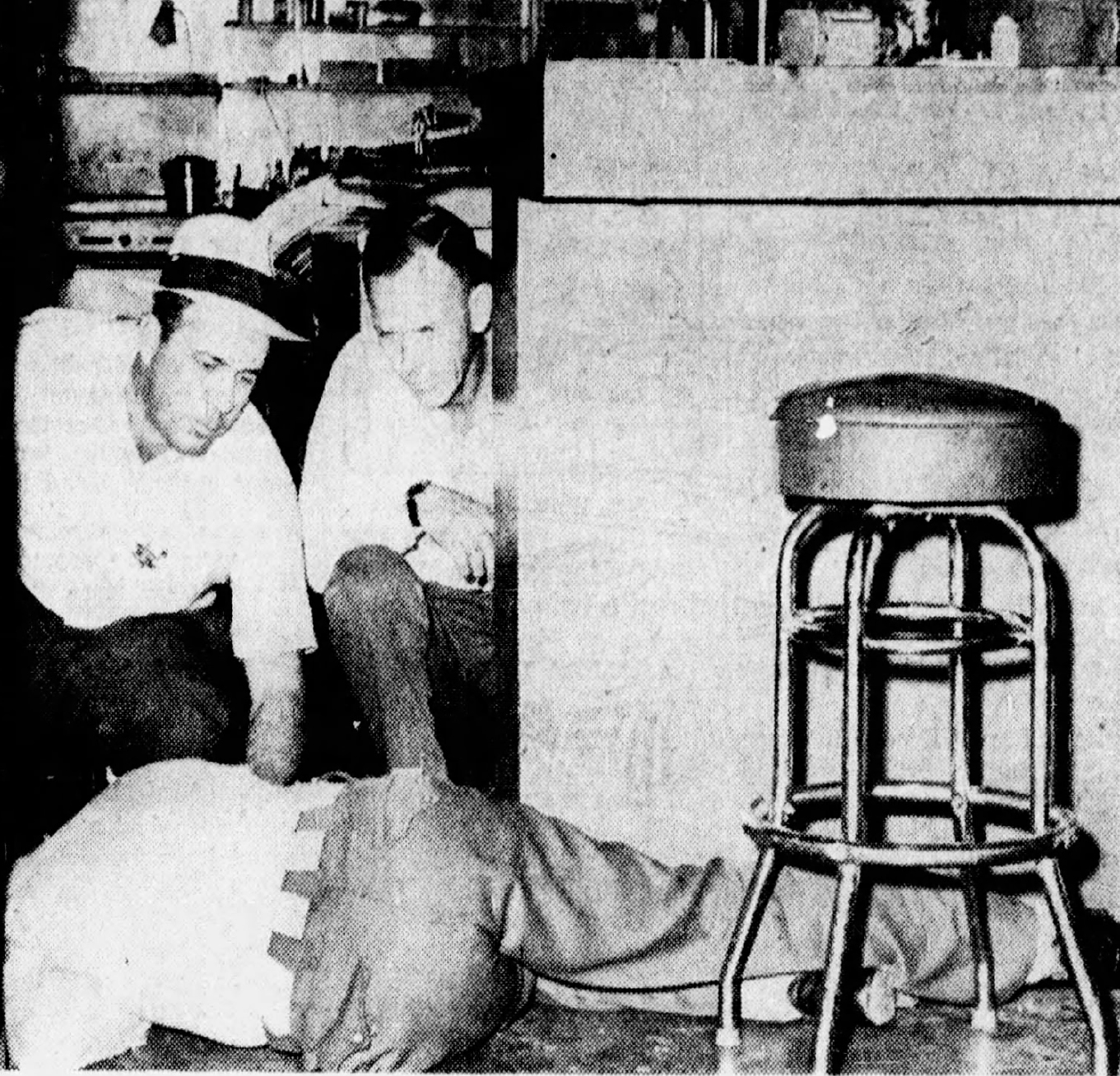

The next morning, little Johnny was the first boy awake. He went over to the car where his parents were sleeping and tried to wake them. Confused, he ran back to his brothers, saying there was something on mommy’s face. Going to check, Jimmy found his mother’s face covered with blood. He lifted his father’s head and found that he too had been shot several times in the head. The little boys tried desperately to flag down help, but several cars would speed past before salesmen and race drivers, Jere Eagle and Dan Cramer from California, stopped and realised the horror of the situation.

Highway Patrolman Dan Birdino and Deputy Sheriff Perry Blankenship were first to arrive on the scene, Blankenship having been notified by his wife, Bertie Lee, after a driver stopped at Johnson’s Café on the east end of Seligman where she worked as a waitress. Bertie would have a bigger role in this story than she could have imagined at the time.

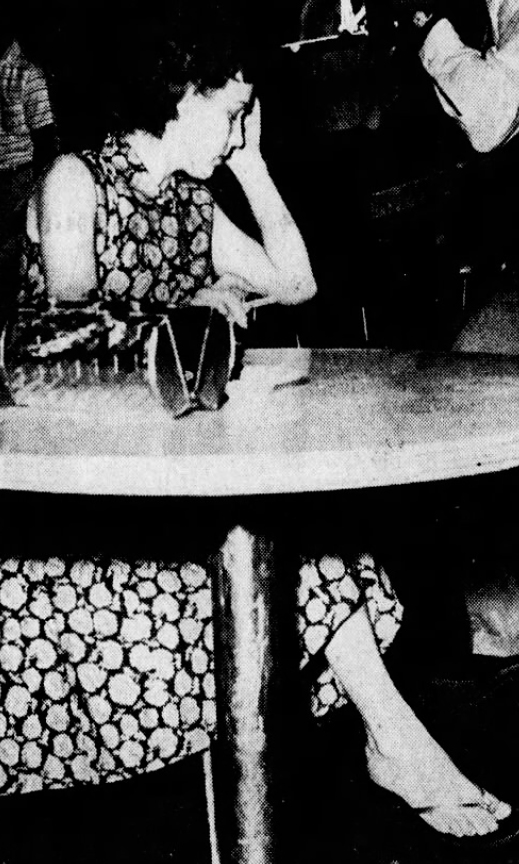

Although around $60 had been taken from JD’s wallet, Utha’s purse, which contained $147, and her expensive jewellery was untouched. Despite a few promising leads – a Greyhound bus had stopped at the same place although this turned out to be some hours after the murders – clues quickly dried up. The best that the local police had was a statement from Bertie Blankenship about a young man she had served late the previous night. He only had a nickel on him, not enough for a cup of coffee, but there was something about him that spooked Bertie so much she gave him the coffee for free. A few hours later, the same man returned to the all-night diner and this time ordered a full meal with tomato juice, paying for it with a $20 note and professing not to recognise Bertie.

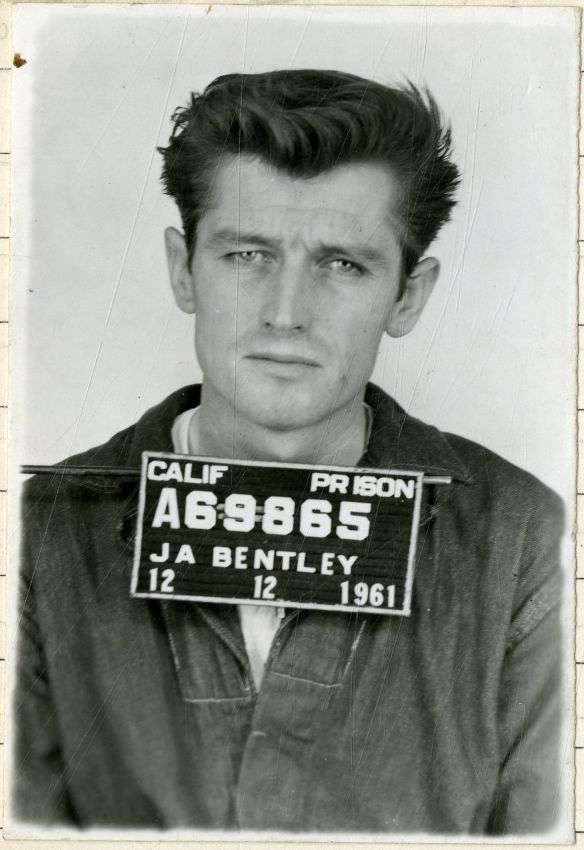

However, a suspect did flag up on the law enforcement radar almost immediately. James Abner Bentley lived in Gilbert, Arizona. However, his mother and estranged wife claimed that he had been in Fresno, California, with them on the night of the murders. Arrested for the robbery and attempted murder of a Phoenix gas station attendant in late June, it transpired that Bentley had been in Fresno – but a month earlier, when he had killed the owner of a liquor store.

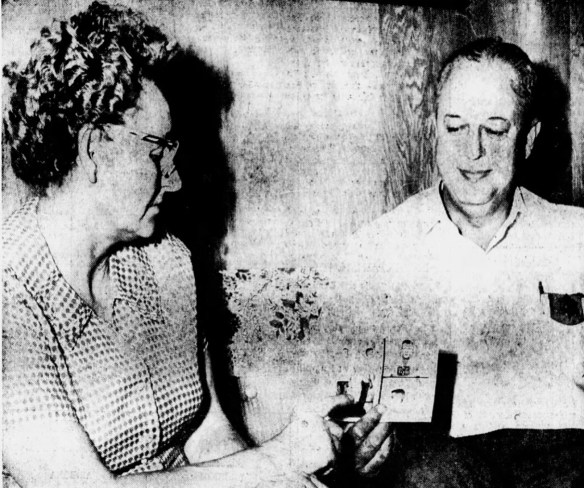

So, James Abner Bentley was already suspected of the Welches’ murders just days after they happened and local Seligman police had a mug shot of Bentley. For whatever reason, no-one thought to show that photo to Bertie Blankenship. Bertie didn’t see a photo of Bentley until a year later after a cellmate of the condemned prisoner had revealed that Bentley alluded to the murders, proudly saying he’d left the children alive. When Bertie was shown an image of Bentley, she immediately identified him as the stranger who had come to the diner – once poor and once with money in his pocket – the night of the murders.

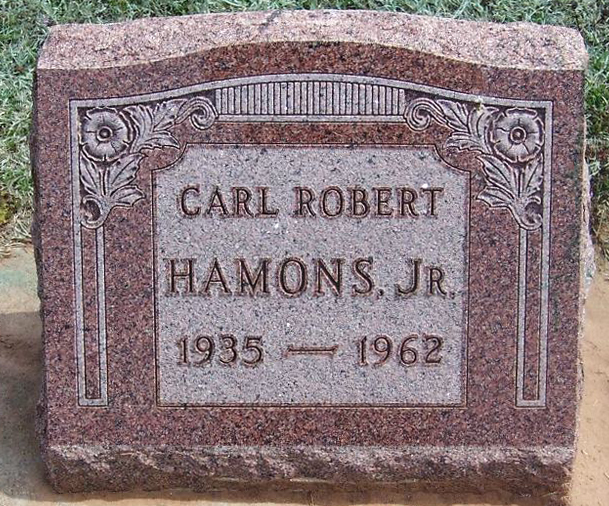

James Abner Bentley was charged with the murders of JD and Utha Welch while on death row in San Quentin, convicted of the murder of the Fresno liquor store owner. Had his death sentence been commuted – and that was a definite possibility at the time as Pat Brown, then Governor of California, was a firm opponent of the death penalty – then Arizona would have proceeded with the prosecution for both the Welch murders and the robbery and attempted murder charge in Phoenix. But, on 23rd January 1963, just after 10am, Bentley went to the gas chamber. It was little consolation to the four small boys (although Jim was, unsurprisingly, a lifelong supporter of the death penalty) whose childhood ended so brutally on the side of Route 66.

It was the work of Seattle advertising man, Boyce Luther Gulley, who, in 1929, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The best hope of a cure then relied upon being in a warm, dry climate, so he moved to Arizona. The only problem was, he didn’t tell his wife, Frances, or his 5-year-old daughter, Mary Lou, where he was going. He simply said he wanted to pursue a life as an artist and drove off in his new Stutz Bearcat. They would never see him again.

It was the work of Seattle advertising man, Boyce Luther Gulley, who, in 1929, was diagnosed with tuberculosis. The best hope of a cure then relied upon being in a warm, dry climate, so he moved to Arizona. The only problem was, he didn’t tell his wife, Frances, or his 5-year-old daughter, Mary Lou, where he was going. He simply said he wanted to pursue a life as an artist and drove off in his new Stutz Bearcat. They would never see him again. It’s thought that Gulley did indeed believe that he had just six months to live and didn’t want to put his family though any suffering (although simply deserting them doesn’t seem to be much of an alternative). Six months passed and then another and he hadn’t died. So it was then that he started upon his life’s work; staking a claim on land close to the South Mountains, he began building what would become an incredible, meandering house with 18 rooms, 13 fireplaces, a chapel and a dungeon. It was built of all types of recycled material – adobe, stone, railroad tracks, telegraph poles, even parts of the Stutz Bearcat when it ceased to be of use – held together with cement, mortar, calcum and goat milk. Gulley, who had had basic architectural training, bartered for materials and also laboured and sold shoes when he needed cash.

It’s thought that Gulley did indeed believe that he had just six months to live and didn’t want to put his family though any suffering (although simply deserting them doesn’t seem to be much of an alternative). Six months passed and then another and he hadn’t died. So it was then that he started upon his life’s work; staking a claim on land close to the South Mountains, he began building what would become an incredible, meandering house with 18 rooms, 13 fireplaces, a chapel and a dungeon. It was built of all types of recycled material – adobe, stone, railroad tracks, telegraph poles, even parts of the Stutz Bearcat when it ceased to be of use – held together with cement, mortar, calcum and goat milk. Gulley, who had had basic architectural training, bartered for materials and also laboured and sold shoes when he needed cash. And for the next 16 years the house grew and grew. However, even with his tuberculosis cured, at no point did Gulley send for his family. Some stories say they believed he was dead, but it seems likely that he did send the occasional letter to Seattle in later years, although without saying exactly where he was (other family members, however, did visit the house, as did many of Gulley’s friends). Then, in 1945, Boyce Gulley died, not of TB but cancer. He left the house to his wife and daughter, along with a mysterious locked trap door and the stipulation that they had to live there for three years before it could be opened.

And for the next 16 years the house grew and grew. However, even with his tuberculosis cured, at no point did Gulley send for his family. Some stories say they believed he was dead, but it seems likely that he did send the occasional letter to Seattle in later years, although without saying exactly where he was (other family members, however, did visit the house, as did many of Gulley’s friends). Then, in 1945, Boyce Gulley died, not of TB but cancer. He left the house to his wife and daughter, along with a mysterious locked trap door and the stipulation that they had to live there for three years before it could be opened. Life magazine covered the opening of the locked compartment, as well as dubbing the place Mystery Castle, although it contained just two $500 bills, some gold nuggets and a Valentine’s card Mary Lou had made for her father when she was a child. Mary Lou stayed on and in fact lived in the house until her death in 2010, although it had no plumbing or electricity until 1992. The accepted story is that this was a labour of love for her on her father’s part, to build her the castle she had always wanted as a little girl. However, I suspect much of this may have been embroidered by Mary Lou to excuse why her father had deserted her; Boyce Gulley seems to have been a selfish albeit talented man who, even after his death, continued to manipulate his family. Mystery Castle is an amazing place, but also a rather sad one; that Mary Lou continued to live in the building seems to be the act of a sad little girl clinging onto an idealised image of her father. I can’t help thinking that, rather than some fantasy building in the desert, she would have much preferred to have her father in her life.

Life magazine covered the opening of the locked compartment, as well as dubbing the place Mystery Castle, although it contained just two $500 bills, some gold nuggets and a Valentine’s card Mary Lou had made for her father when she was a child. Mary Lou stayed on and in fact lived in the house until her death in 2010, although it had no plumbing or electricity until 1992. The accepted story is that this was a labour of love for her on her father’s part, to build her the castle she had always wanted as a little girl. However, I suspect much of this may have been embroidered by Mary Lou to excuse why her father had deserted her; Boyce Gulley seems to have been a selfish albeit talented man who, even after his death, continued to manipulate his family. Mystery Castle is an amazing place, but also a rather sad one; that Mary Lou continued to live in the building seems to be the act of a sad little girl clinging onto an idealised image of her father. I can’t help thinking that, rather than some fantasy building in the desert, she would have much preferred to have her father in her life.