On the edge of Joseph City, Arizona, on an orphaned stretch of Route 66, stands a ruined trading post. Until last year, the remains of a sign announced that this was once Ella’s Frontier. When people speak of this place, they mention Ella Blackwell and her eccentricities, but her husband (from whom she won the trading post in a divorce settlement) is generally just referred to as a ‘bandleader’. Ray Meany was far more than that.

Born to an Irish father and Spanish mother, Ray Meany was a sailor, musician, composer, teacher, publisher, author and motel owner. Oh, so many motels! He hadn’t even reached his teenage years before he lost his father in the Great War; however, as soon as he was old enough, Ray joined the Merchant Marine and for twelve years he travelled the world. While in Hawaii he fell for a hula dancer. The romance quickly fizzled out but Ray had fallen in love with the island. On board ship, he talked constantly of Hawaii and of its music until one of his shipmates gave him a cheap guitar and bet him that he couldn’t learn to play it.

Not only did Ray learn to play that guitar, he learned to play it well. When he left the Merchant Marine, he started a steel guitar school in Oakland, California, where he introduced the lilting sound of Hawaiian music to pupils. Eventually the Honolulu Conservatory of Music of which he was the Director had some 70 branches and over 5000 pupils. In addition to the school, Ray had his own recording studio, music publishing company (which included many of his own compositions), organised large events, had his own band and produced the Music Studio News magazine. Even a brief sojourn to serve in the Second World War didn’t get in the way of his music – while serving at Camp Fannin, Texas, he continued to write a column for a national music magazine and was popular with all at the base.

After the war, his music schools went from strength to strength and Ray might indeed have built a musical empire but for a fateful meeting with a woman who changed his life. Polish-born Ella Lenkova (who had come to the USA as a small child under her original name of Aniela Lenosyk) was a musician in her own right. She would claim later that she had trained at the Julliard School of Music and there’s probably no reason to doubt that. She wrote and arranged her own songs, among them Aloha Lei, My Hula Sweetheart and Goodnight And My Aloha To You and, as Ella Maile Blackwell (Blackwell was her first married name) she was the New York correspondent for Ray’s Music Studio News. She is still mentioned under that name in a Hawaii newspaper in April 1950, but by October of that year, as she descended the steps of a Pan-Am air plane at Honolulu airport, she was Mrs Ray Meany. Interestingly, although Ray was a regular name in his local newspapers which he courted and that followed his career and achievements keenly, there was no mention of his marriage, nor of Mrs Meany.

Ray may not have known it then, but his life was about to change forever. It was still full steam ahead with his business and in 1951 he opened a new $100,000 Hawaiian music centre on Foothill Boulevard in Oakland where the building still stands. So it was a huge shock to all of his friends and pupils when he announced that he and Ella would be moving to Arizona to run a trading post. Ray explained that he felt he had a calling to help the Native Indians, saying, “I got tired of the hoopla of entertainment. I felt that there was so much I could do in Arizona among the Indians.” While Ray did indeed work hard on behalf of the locals, instigating a school and roads for the Indian tribes, the real reason was more prosaic. A jealous Ella didn’t want him mixing with the musical crowd or going off to Hawaii with his band. He would admit later in life: “Hawaiians are very affectionate people. They hug and kiss you at the slightest provocation. My wife was jealous, so I gave up the music business to keep my wife. But she didn’t like Indians either, so we separated.”

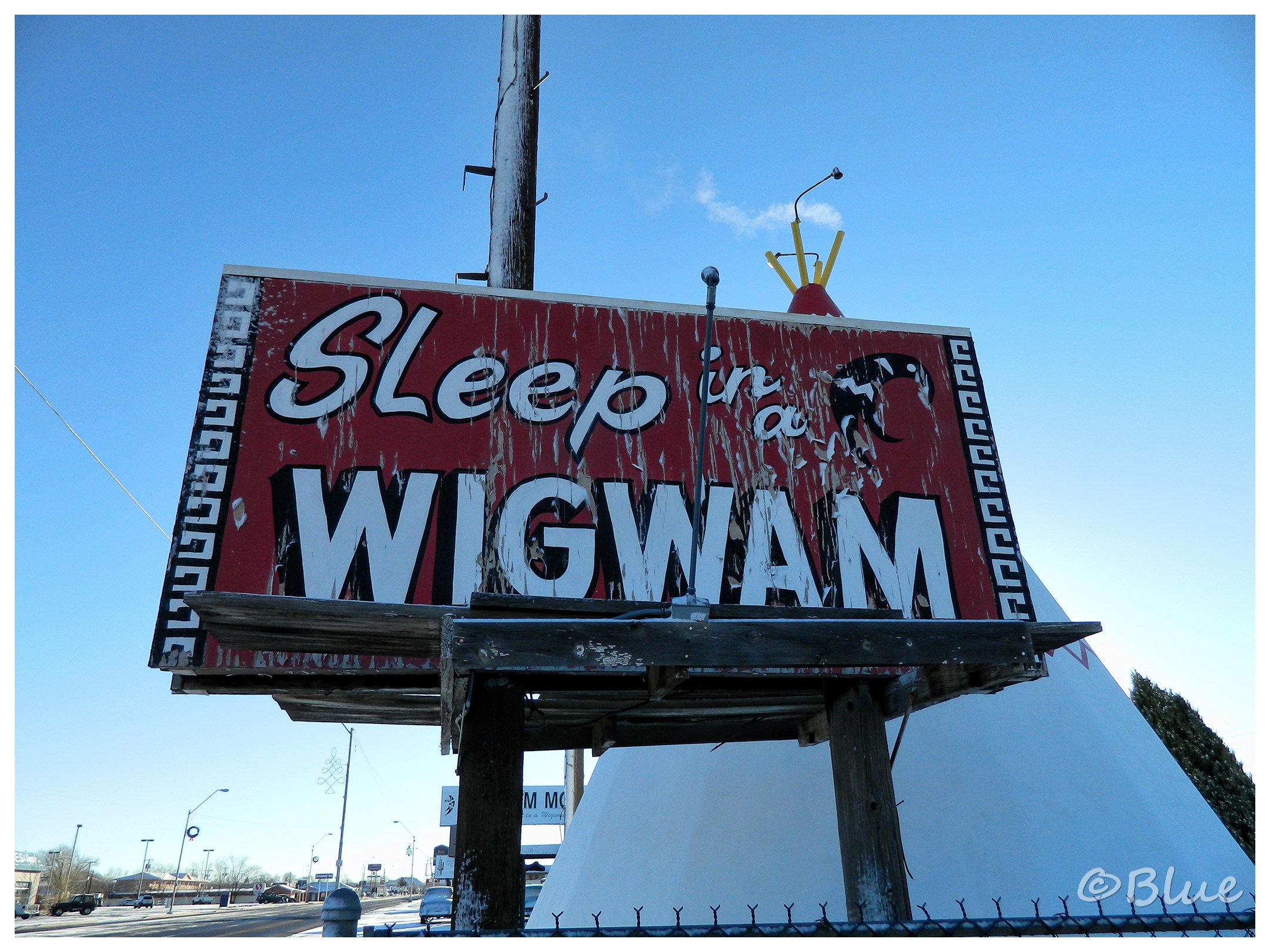

For a couple of years, Ray and Ella ran the Hopi House Trading Post at Leupps Junction on Route 66. It was several cuts above the average trading post with a motel, trailer park, café and curio shop with murals by local artists. The grand opening of the refurbished Hopi House was on 20th March 1954, but, within a couple of years, the Meanys would be divorced. They may already have owned the Joseph City trading post (then called the Last Frontier) or Ella may have purchased it with a divorce settlement, but it seems dubious that they bought it in 1947 as several books claim. It’s very unlikely that they were married then and Ray was still expanding his music career at that time.

It was at this point that Ray embarked on an almost manic buying and swapping of motels that would continue for years. It was if, adrift from his beloved music, he couldn’t find anything to give him roots. After running the Hopi House on his own, he exchanged it for a motel in California in 1957. By January 1958 he had swapped that for the Rancho del Quivari, 65 miles south west of Tucson. He was there for less than a year, selling up and buying the Copperland Motel in Miami, Arizona in November 1958. A few months later he swapped that for the Shangri-La Motel in San Diego, but by the end of December 1959 he was in the La Casita Motel in Twenty Nine Palms. He didn’t settle there either, buying the Desert Vista Motel in Benson, Arizona, where he told a local newspaper, “I think this is it. I intend to stay in Benson.”

But just weeks later, in June 1960 he had sold up and bought the Sun Set Motel in Sedona where he managed to stay for two years, moving to a motel in Texas in July 1962. There were probably others in between, but in 1969 he was in Arkansas, desperately trying to sell the Riverside Motel in Lake Greesonak. Eventually he did, but at a loss. During this time, he had kept his contacts with the music industry and every once in a while might compose another song, but the glory days were over, although one of his songs, Hula Lady, was a big hit in Japan in the early 1980s. He tried his hand at writing once more, publishing Fasting and Nutrition, Vital Health, a book of the philosophical musings of Chang, his Lhasa Apso dog (who, by now, had been dead for twenty years) and a title called Vacation Land.

But he still seems a man who was never able to settle down again. In autumn of 1975 Dr Elva S Acer offered him a job managing her Vita Del Spa in Desert Hot Springs, California. He was initially enthusiastic, even attending courses on the spa’s treatments, but by January 1976 he had taken off again. His last years were spent in various country clubs in Florida although he came back to California at the very end of his life, dying in Napa on 29th July 1987. His ex-wife had preceded him in death three years before, having never moved from the Joseph City trading post. Her headstone reads ‘Ella Meany Blackwell’; Ray Meany’s grave in St Helena Cemetery, Napa County, has no marker.

A dapper Ray Meany, returning from his time as an enlisted solder.

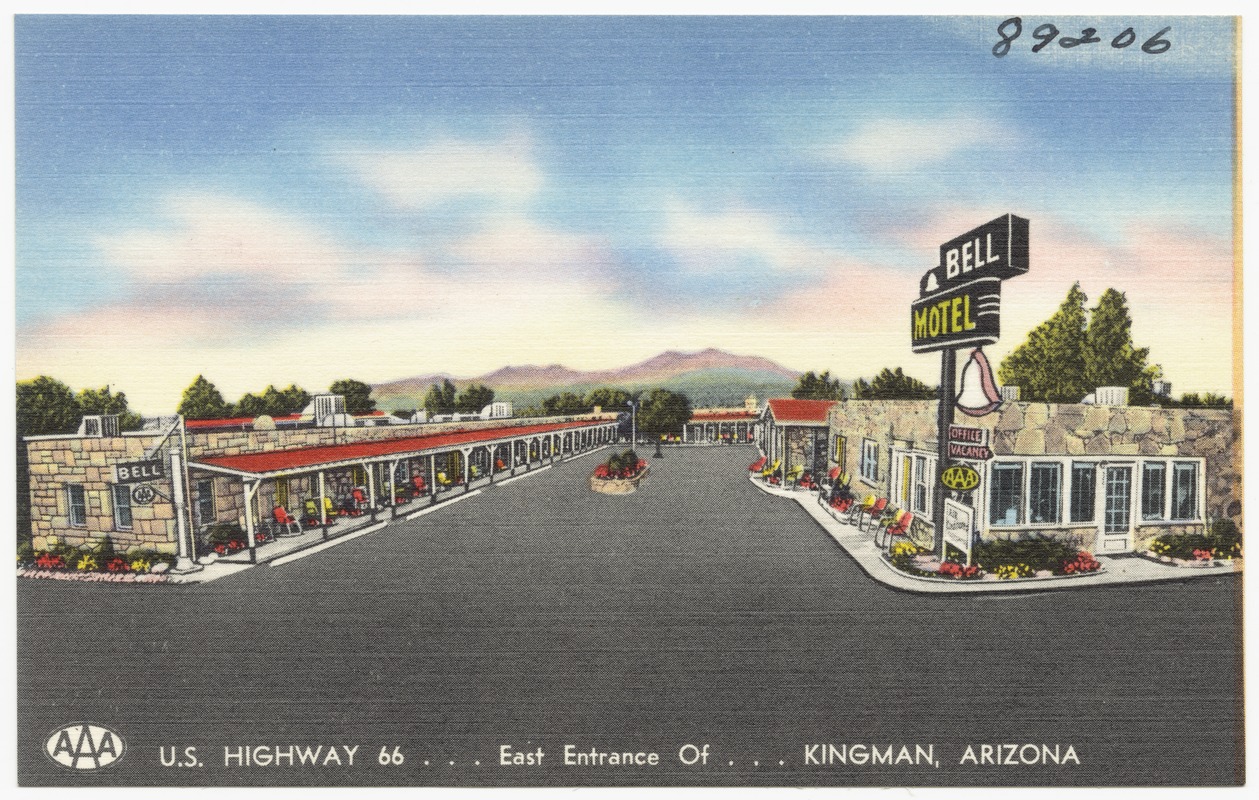

In 2012, a state-wide survey for the Arizona State Historic Preservation Office recommended that the by now boarded up Desert Lodge Apartments should be put forward for entry onto the National Register of Historic Places with ‘High Priority’, this rating means it filled one or more of the following criteria: an excellent example of its property type and strong Route 66 character; particularly rare property due to age, type of construction or architectural style; good intact properties which appear endangered due to deterioration or redevelopment and/or being sited in a high priority historic district. Even in its sad state, with its ‘giraffe’ stone façade, the motel ticked at least two of those boxes.

In 2012, a state-wide survey for the Arizona State Historic Preservation Office recommended that the by now boarded up Desert Lodge Apartments should be put forward for entry onto the National Register of Historic Places with ‘High Priority’, this rating means it filled one or more of the following criteria: an excellent example of its property type and strong Route 66 character; particularly rare property due to age, type of construction or architectural style; good intact properties which appear endangered due to deterioration or redevelopment and/or being sited in a high priority historic district. Even in its sad state, with its ‘giraffe’ stone façade, the motel ticked at least two of those boxes. In April 2015, the Californian owners announced they would be gutting the property, leaving the stonework standing and it would then be redeveloped as living accommodation. The interiors were indeed gutted and all the woodwork ripped out, and then nothing else happened. For a year, the Desert Lodge Apartments have stood, denuded and fenced off, and I’ve hoped against hope that the planned renovation would take place.

In April 2015, the Californian owners announced they would be gutting the property, leaving the stonework standing and it would then be redeveloped as living accommodation. The interiors were indeed gutted and all the woodwork ripped out, and then nothing else happened. For a year, the Desert Lodge Apartments have stood, denuded and fenced off, and I’ve hoped against hope that the planned renovation would take place.