Still looking very much as it did when it was built over 80 years ago, but the Riviera Courts is in bad shape.

In 1937, the newly opened Riviera Courts was one of the swishest places to stay in Miami, Oklahoma. With its wide V-shape, its white Mission Revival look and being placed on the curve of the road, it was designed to be conspicuous to travellers in both directions and, like many other motels, its destiny was inextricably tied to that of Route 66. It was built at the south west end of Miami at a time when virtually all the local motels were situated at the north end of town; the reason why lies with the date of when it opened. 1937 saw the opening of a new bridge over the Neosho river and a new alignment of Route 66. That traffic would run right past the Riviera Courts and for years it brought in motorists.

The motel had not only garage bays, but doors on those bays, too.

One of the elements of the Riviera Courts was that, next to each of the fifteen rooms, was a garage bay for the resident’s car. Not so unusual, except for the fact that the Riviera Courts’ garages had doors which was a feature rarely seen on motor courts of the time. Passers-by today might assume that those bays have been fitted with doors in modern times for the purposes of storage, but that’s not the case. The Riviera Courts looks very much as it would have done in the 1930s and ‘40s and, on most of the garages, there still exists the original sliding doors mounted on an overhead track.

A postcard of the 1940s states that the Riviera Courts was ‘All brick, modern, 100% fireproof with automatic steam heat, tile showers, Beautyrest mattresses, with cross ventilation and ventilating fans.’ The motel passed through several hands, for example, Mr and Mrs PA Janson, and then, in 1952, Adam Ried and his wife although they seem to have quickly passed it onto NC Sawyer. He would subsequently sell the motel to Marion and Nolah Roberts in February 1956 who gave him a promissory note and chattel mortgage on the property. The problem was that the Robertses then didn’t pay.

Sawyer took Marion and Nolah Roberts to court for the sum of $69,500 (which indicates they had never made a single payment). Nolah Roberts’ defence for not paying was that Sawyer had neglected to mention the Riviera Courts had been flooded by the Neosho river during the Great Flood of 1951 which killed 17 people, displaced over half a million others and resulted in millions of dollars worth of damage. Was the Riviera Courts under water? If so, surely it would have been restored in the intervening five years (during which time major flood preventions were also put into place to ensure it wouldn’t happen again).

The opening of the Will Rogers Turnpike would be the beginning of the end for the Riviera Courts.

Perhaps more telling for the defaulting on the motel’s mortgage is that, just months after Nolah Roberts (and it was very much her project) agreed to buy the Riviera Courts, the Will Rogers Turnpike opened, bypassing Miami. Mrs Roberts may not have anticipated just the effect that this would have on the motel and either wouldn’t or couldn’t pay. Sawyer was charged with perjury in 1958 on the ground that he did indeed know about the flooding but by then the Rivera Courts had been foreclosed and was the subject of an auction in November 1958. Sawyer had tried to sell the place in May of that year with no luck.

These were clearly not good years for the Robertses. In April of 1958, Marion Roberts was implicated in a land development scandal in which Cinema-Surf took several thousand dollars from investors for a half-a-million dollar scheme to build a luxurious drive-in theatre, swimming pool and amusement park in southern Oklahoma. Roberts handled the stock sales through his company Marion L Roberts Brokerage Co in Oklahoma City – or at least he did until the company’s license and bond were cancelled in 1957 – while his son, also called Marion, was the main stock salesman for Cinema-Surf.

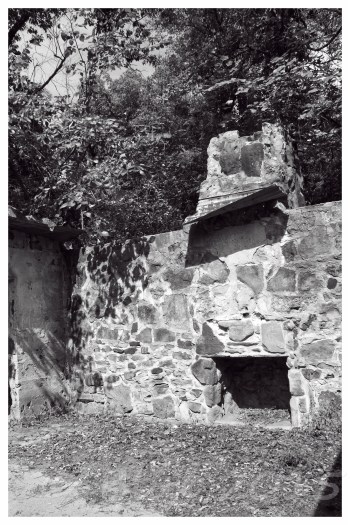

One wing of the Riviera Courts. The building to the right was the living quarters and office of the owners.

From then on, as is so often the case, the motel went downhill. It was renamed as the Holiday Motel – probably trying to cash in on the popularity of the Holiday Inn hotel chain – and would struggle on for another two decades, filling its rooms with long term residents, until it finally closed in 1978. It was a private residence for a while, as well as being listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, but it has the air of general desertion each time I’ve passed recently. In a town which has devoured or demolished most of its Route 66-era motels, Miami’s Riviera Courts deserves to be saved and cherished.

This stylized postcard seems to be the only image of the Riviera Courts. It dates to around 1951 or ’52 when Mr and Mrs Adam Ried were the owners and operators. Postcard by kind permission of Joe Sonderman.