The ‘Seniors 38’ stone outside the one-room jail in Texola.

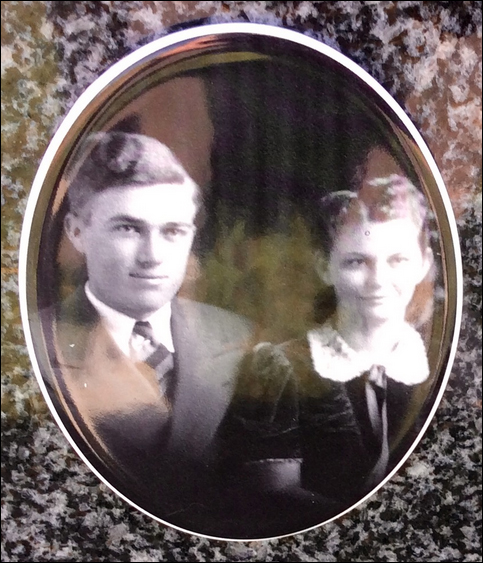

LOIS WIGLEY

Lois Wigley was born on June 23, 1919, to Thadeus Park and Ollie Wigley, two years after her brother Robert. She was known as ‘Kitten’ from a young age and was active in school activities, especially those involving performing. Before enrolling at Texola High School, she was educated at Erick High School where, in 1935, she was Point Secretary of X-Mu, a society for students with a B average; Parliamentarian of the Rainbow Club; President of the Dinner Bell Club; founder of the Coo Coo Club and a member of the Glee Club. Texola might have seems a little dull after that!

Lois Wigley

Just days after graduating she married Gerald Bibb on October 18, 1938. Gerald had been at school in Sayre and been as active as his bride – he’d been the President of his senior class and a schout master. After graduation he had intended to attend the Cincinnati College of Mortuary Science and become an undertaker. But the couple stayed in Sayre after their marriage with Gerald first managing a gas station and then owning and operating Bibb Ditching and Constriction Company. They had two children, Bobby Gerald, born on August 27, 1940, and Kenneth ‘Kenney’ Thad on July 11, 1943. Gerald enlisted in the US Army in February 1944 and served for two years. An accomplished pilot, he was instrumental in developing the Sayre Municipal airport and had served as a Trustee of the Airport Commission. ‘Kitten’ died on August 28, 1992.

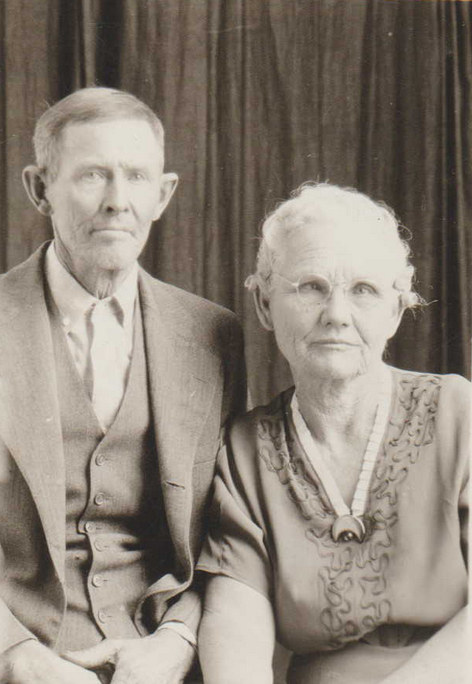

VENICE SLOSS

Venice Sloss was born on January 9, 1917, to George Benson ‘GB’ and Laura Sloss in Shamrock, Texas. She married a mechanic called Robert Lee Wright on July 27, 1940, and they had four children, three daughters and a son. But the marriage ended in divorce in October 1969. Robert Lee remarried, this time to Ruth Henry, but died of stomach cancer in 1977. Venice moved to Amarillo where her youngest daughter Ethel Elizabeth lived, and spent her later years quilting, crocheting, gardening and being a grandmother and great grandmother. She died on February 22, 2008 having outlived two of her children, Rovena who died in 2004 and Doiel Wayne who passed away in 2005.

Venice Sloss

JIMMIE POWERS

Jimmie Arnold Powers was born to James Andrew and Minnie Belle Powers in Heavener, Oklahoma, on October 7, 1919, the youngest of ten. His father was a farmer and several of his older brothers worked on the farm.

When Jimmie was just seven, the family was devastated by an appalling tragedy; Jimmie’s oldest brother William Walter ‘Bud’ had gone off to be a fireman on the railroad. On September 18, 1927, while he was acting as fireman on a Kansas City Southern freight train, the boiler of engine number 710 exploded near Marble City, Oklahoma. Bud suffered terrible injuries and died the following morning while the locomotive’s engineer lingered another week; both men were from Heavener. 27-year-old Bud left a wife and a seven-year-old son, LD Eugene. (In a horrible twist of fate, LD was killed while acting as tailgunner on the B-29 ‘Devil May Care’ which was shot down over Siam in 1944. He had just turned 25.

Jimmie actually graduated in 1939, a year after most of the others on the stone, which seems to indicate that this was a group of friends rather than the actual class.

Like his nephew, Jimmie too would enlist and served in the army for over four years, finally being demobbed on August 29, 1945. He married Katherine McManamon and they lived in Ohio where he worked as a wire salesman before moving to California. He would marry again in 1979 and died on May 12, 1985.

RUBY BARTLETT

Ruby Ellen Bartlett was born on May 4, 1920, in Texola to Luther and Stella Bartlett.

In 1935 she was a member of the nearly formed Texola High School girls’ Glee Club, along with fellow class members, Johnnie McSpadden and Doris Nelms. The same year, she was one of 15 Texola freshmen who made a two-day trip to Oklahoma City (others included Doris Nelms, George Blair, Wintha Doss and Herbert Copeland). It seems that only the star pupils of the school were selected for the trip in which they stayed at the Skirvin Hotel and visited some of Oklahoma’s important institutions and industries. Later that year she was picked to be one of the school’s librarians and, along with Jack Loftis and Lois Wigley, was in the Senior class play (it was called ‘George in a Jam’ and was billed as ‘a three-act comedy that will keep the audience in an uproar from the rising of the curtain’).

The youngest of Stella and Luther’s four children, she had three older brothers, but was closest in age to Ernest. He was just three years her senior and it must have been devastating when Ernest was killed in a car crash when Ruby was 17.

In 1939 Ruby went to the Southwestern College of Diversified Occupations, but in November her father Luther died suddenly from a single shot from a .22 calibre rifle. The coroner adjusted that it had been an accident, Luther having grabbed his rifle by the barrel from his wagon and the trigger catching on something.

On August 30, 1941, in a dress of royal blue velvet with a bouquet of pink rosebuds and to the accompaniment of violin and accordion music, she married George Benson ‘GB’ Sloss Jr of Shamrock, Texas. If that name sounds familiar it’s because GB was the brother of Ruby’s classmate, Venice Sloss.

Wedded life was put on hold when GB joined the 313th Engineers Combat Battalion in 1943 and went off to Italy as part of the 5th Army. He would not return to Texola until November 1945. GB and Ruby settled down to a life ranching, raising pigs and growing alfalfa and peaches, although she continued to be an active member of the community, helping in the First Baptist church of Texola and being a member of the Bulo Home Demonstration Club. Their first child, David, was born on October 25, 1946, followed by a daughter, Martha.

Stella had signed the farm over to her daughter shortly after Ruby was married, living with the newlyweds but, on December 19, 1953, GB sold off everything on the farm, from the livestock to machinery to a lot of canned goods. Just a month before, the family had moved to Modesto, California, where GB had taken up a job with a food processing company. Whatever the reasons, the move didn’t work out and GB, Ruby and children were back in Texola less than a year later. They then moved to Shamrock, although Stella stayed in Texola.

In 1966 David joined the US Air Force and went on to train as a munitions specialist. He was assigned to an airbase in Okinawa, Japan, where he spent his career, married and continues to live.

Then, at 3pm on August 31, 1981, weeks before their 40th wedding anniversary, GB put a gun to his head and shot himself dead. Ruby’s mother, Stella, lived to the age of 101, dying in 1990 after which Ruby moved to Pampa, Texas, where her daughter and son-in-law lived. She passed away in 2014 at the age of 93.