Ed’s Camp, east of Oatman, Arizona, at the foot of the Sitgreaves Pass, is fascinating for the man who was the only owner; Lowell ‘Ed’ Edgerton, a man of both enigma and mystery who has left behind him one final puzzle.

Edgerton was born in Michigan in 1894 and headed west as a young man on the advice of his doctor. Edgerton had suffered from tuberculosis which, at the turn of the 20th century, was the leading cause of death in the United States – he claimed exemption from the draft in World War I as a consumptive. Initially moving to southern California, he found the climate of Arizona more to his liking and he would spend the next sixty years of his life in Mohave County.

Little is known about Edgerton’s early years in the West and many of the stories he told throughout the years should probably be taken with a healthy dose of salt. Later he would claim that he had begun to train as a doctor (he did study for a short time at the University of Michigan although that was in engineering) and had, while working for a mining company in Mexico, amputated a man’s leg during the Mexico revolution of 1910-1920. He told stories of how he had owned a mansion in Los Angeles but had lost it in a property deal that went bad. He also claimed that, while tracking a mountain lion, he followed the beast into Nevada and became so engrossed in the hunt that he forgot about his wife and five children and figured there was no point in going back. There’s actually no record of Edgerton ever having been married, let alone having a brood of five children!

When he moved to the Oatman area, he was able to pick up the lease on the tailings dump of the Oatman works, tailings being the by-product of the mineral recovery process, the material left over after the valuable ore has been separated from the uneconomic material. Within months, his operation was making more money than the whole mine and he was then hired by the Tom Reed Mine as foreman of recovery. Around 1919, Edgerton bought a parcel of land at Little Meadows in the foothills of the Black Mountains in north west Arizona. The site had been known to Europeans since 1776 when Father Francisco Garcés, a Spanish missionary and explorer, paused here on his expedition across the south west of America, while it became a staging posting for future treks, including that of Lieutenant Beale. The attraction of Little Meadows was that it had that commodity which could be worth as much as gold: water.

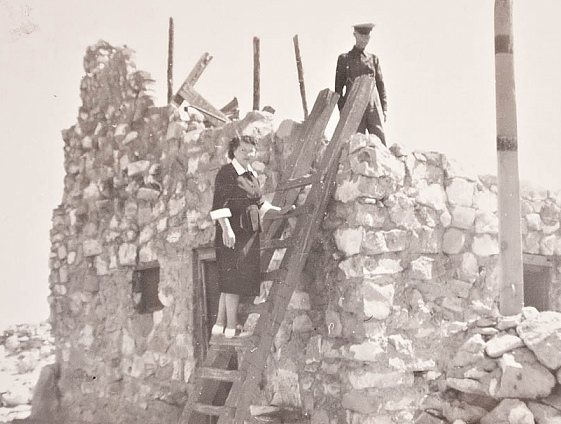

Initially, like so many who rushed to the area at this time, Edgerton’s intention was to make his fortune through a gold strike. With his older brother, Tibor, he took on a number of mining jobs until he realised that he could make a steady (and easier) living catering to travellers and miners than digging into the mountains. His trading post was little more than an open space with a tin roof – he later said that, with the inauguration of Route 66 in 1926, traffic became so busy so quickly that he never had time to add walls! As Tibor returned to Kalamazoo, Michigan, to open a tea rooms, Edgerton added the Kactus Kafe (this time a proper building) and a gas station and called the place ‘Ed’s Camp’.

At first Ed’s Camp had no tourist cabins or rooms. Instead, travellers could pitch a tent or sleep in their cars. For those who wanted a little luxury and had a little more cash, there was a screened porch where they might sleep on a cot. Just as NR Dunton did at Cool Springs, Ed charged for water on a per bucket basis although that fee was waived if people paid to stay. As the place grew, a grocery store and souvenir shop were added and Ed’s Camp became a stop for Pickwick Stage Lines, a coach company that would become part of the Greyhound bus empire.

But Ed Edgerton was far more than just a store and gas station attendant. Over the years, he studied the rocks of Arizona and became an expert geologist who could identify any Mohave County rock and say, to within a few miles, from where it had come. He proudly told people how he had met Marie Curie, the French-Polish physicist – a claim which is quite possible as Curie toured the United States in both 1921 and 1929.

Edgerton owned and mined a rare earth mine from which he extracted ore that was shipped to a variety of companies, providing some thirty different minerals that were used in alloy steels, electronic components, ceramics, plastics, atomic devices and even cosmetics. He even, if only briefly, had a mineral named after him, although Edgertonite, an oxide of oxide of iron, yttrium uranium, calcium, columbium, tantalum, zirconium, tin, and other minerals was quickly renamed Yttrotantalite when it was realised it had already been discovered in Sweden in 1802. It is, however, quite likely that Edgerton was the first man to find Yttrotantalite in the United States and he would say that he had provided the material for the first atomic bomb. Truth or fiction? We shall probably never know.

Edgerton credited Yttrotantalite with saving his life. According to him, on 17th April 1957, doctors told him he had cancer. They gave him thirty days to live unless he had major surgery. Edgerton declined the operation and returned to Ed’s Camp where he decided he would treat himself. The story changed in some details on each retelling, but this is probably the most comprehensive description to survive: “I put on two suits of heavy woollen underclothes and put these swatches [of Yttrotantalite] in between, all around, and then I put three big electric pads around that. I cooked myself for about seventy-two hours at one hundred and thirty degrees. I didn’t eat anything, I drank warm water. At the end of seventy hours stuff began to loosen inside me … Rotten goddamn stuff, it couldn’t take the heat. I commenced to bleed internally and for up to ninety hours I bled inside – rotten blood first and then fresh blood – and then that quit.”

After that, Ed Edgerton nursed himself back to health on a diet of goat’s milk, raw eggs and avocadoes. Two months later, his doctor declared there was no sign of cancer in his body and it was a miracle. Although it’s tempting to believe that it would be difficult for anyone to survive such extremes of temperature for so long, not to mention four days of internal bleeding, Edgerton believed that he had cured a cancer and instead of having just a month left on this planet, he lived for another thirty years. He claimed that he was studied intensively by the Veterans Administration Hospital in Fort Whipple, near Prescott, although there are no records of Edgerton having been a patient until he died there in 1978. He also told people he had worked with one of the foremost cancer experts in the world – although he declined to name the scientist – as well as claiming that he could predict where in a person’s body a cancer might be just by the colour of their hair.

It would be tempting to dismiss Ed Edgerton as a crazy old desert rat, telling tall tales in the best tradition of a hermit. But Edgerton was far from that. While some of his stories may have been embellished – and others, quite frankly, tongue-in-cheek fabrications created to entertain visitors – he was much respected in the fields of geology and mineralogy, despite his lack of formal training. He took on consultancy work for companies, taught in the local college and wrote and presented papers on minerals. Edgerton was certainly not a hermit although much about his life remained a mystery. In 1948 he ran for the office of state senator in Mohave County on a Republican ticket (although he was beaten by the Democratic candidate, C Clyde Bollinger) and he trained to be a census enumerator for the 1960 US Census, a job his father had also done in Michigan sixty years earlier.

Thanks in part to the natural springs and in part of the improvements that Edgerton made over the years to the water flow, Ed’s Camp truly became an oasis in the desert. Late into his seventies, Edgerton kept Kingman supplied with pears, as well as growing apricots, tomatoes, quinces, strawberries, peppers, corn and grapevines. His pomegranates were so good that they won four ribbons at the Arizona State Fair! He even managed to keep alive a huge saguaro cactus which stood for years just by the gas pumps. It eventually attained an impressive height and several arms before dying around thirty years ago.

On 7th September 1978 Ed Edgerton died at the age of 83, not as he would have surely wished at the place he had called home for most of his life, but in the VA Hospital in Fort Whipple. His obituary mentioned only that he was a ‘retired miner’ but Lowell Edgerton was so much more than that. Today Ed’s Camp is gently decaying although the rigid enforcement of those NO TRESPASSING signs mean that he would still recognise the place. The gas pumps and cactus are long gone but the makeshift trading post and the café remain, while you can catch a glimpse from Route 66 of the basic tourist cabins he built. Squint hard at the hillside opposite and you might just make out the few remaining white stones that once spelled out Ed’s Camp. Now it seems a bleak spot in the desert but for much of the last century it was paradise for Ed Edgerton.

But Lowell Leighton Edgerton leaves behind one last mystery. Just where is his final resting place?

The Findagrave web site has him listed being buried in the Mountain View cemetery in Kingman, which would seem logical. So just a few weeks ago I took a walk around to see if I could find his grave. When I had no luck, I wondered whether it was unmarked, so I sought the assistance of the cemetery staff. They were very helpful and hauled out large leatherbound ledgers which list all of Mountain View’s ‘residents’. Finally they looked up and said, “He’s not here.”

As Ed died in a VA hospital I considered whether he would been buried by the Veterans Administration in Prescott. But, after combing through VA records for all of its Arizona cemeteries and burials, I drew a blank. I widened it to a nationwide search (although it seemed supremely unlikely he had been taken back to his home state of Michigan) and the end result? He wasn’t there.

Wherever Lowell Edgerton was laid to rest, he’s keeping it to himself – and I think he would rather have liked that.