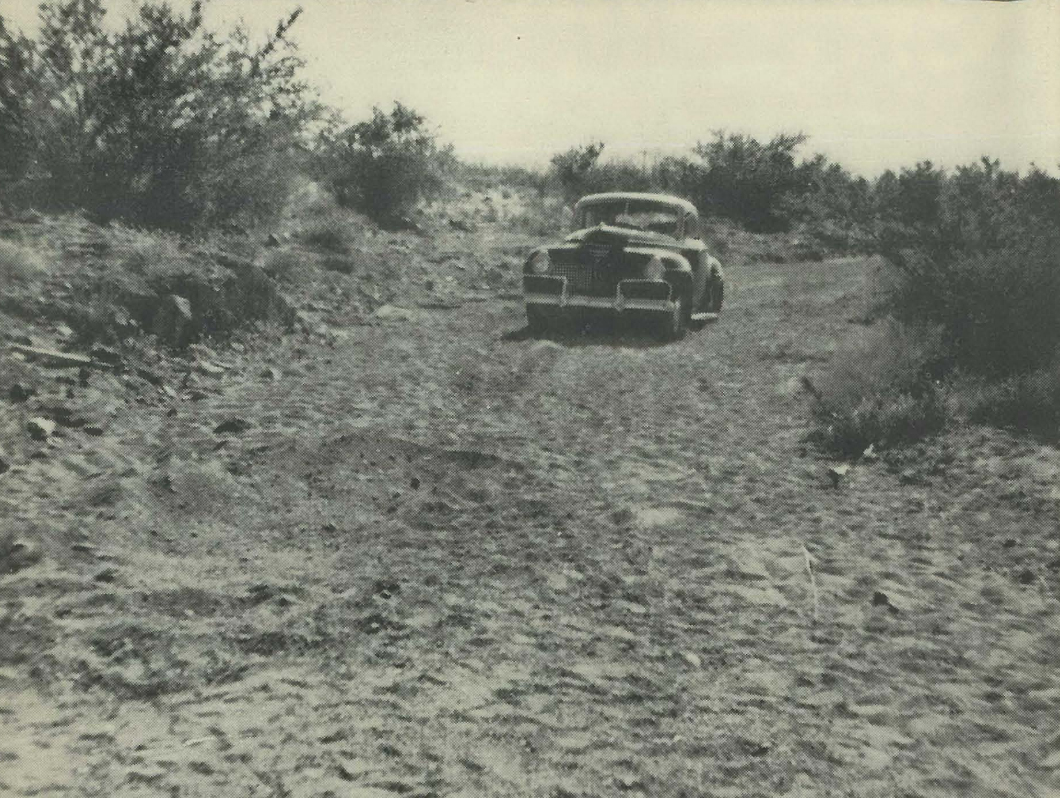

It was the afternoon of September 4, 1945, and an Arizona Highway Department workman was working on Route 66, around 16 miles west of Kingman on the road towards Oatman. The previous day he’d noticed a car stuck in a sand wash the previous morning and thought little of it. But when it was still there the following afternoon he reported it to the Sheriff’s office in Kingman.

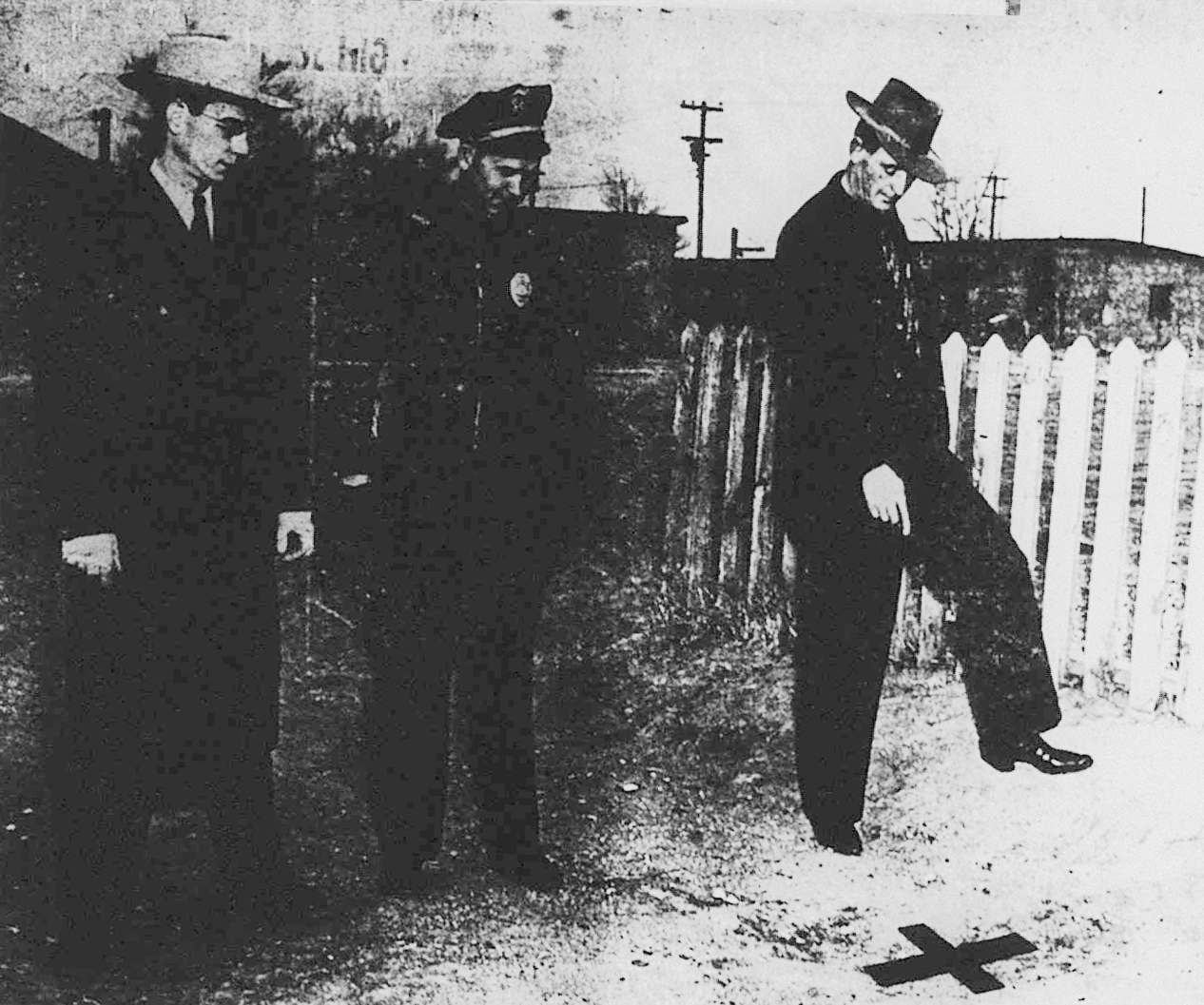

Sheriff Frank L Porter drove out on Highway 66 to inspect the car, expecting nothing more than the misadventure of a traveller. But when he spotted a lady’s black patent leather purse on the rear seat of the 1941 DeSoto Club coupe, he was more concerned – what lady leaves her purse behind? The question was answered a few minutes later when, a few feet in front of the DeSoto, officers spotted a mound of sand – with two fingers protruding from the dirt. They were the ring and left middle finger of a woman, complete with gold wedding band and gold ring with a diamond.

The makeshift grave was revealed to contain a woman of around 30 years of age, about 5 feet six inches in height and around 125lbs in weight. She was wearing blue ladies’ overalls and bobbie socks and had brown hair. Wrapped around her head was a man’s maroon and yellow checkered sports shirt; it was bloodstained, as was the powder blue ladies’ coat that partially covered her and the rear seat and interior of the car. A pair of man’s shoes was also found in the car, the soles covered in oil.

The maroon DeSoto with its tan top was registered to a WM Cole of 1515 East 87th Street in Los Angeles but there was no sign of Mr Cole. The car was filled with cardboard boxes and personal belongings and, from their contents, officers found they belonged to mother of two, Alline Alma Cole, 27. At first, her missing husband came under suspicion – until police found there had been a third person in the car.

A small suitcase in the car contained the personal effects – which included divorce papers and letters to a waitress in San Jose, California – of one Emmett Edwin Patterson. Better-known as Ted, Patterson was Mrs Cole’s brother. The Coles had been living in Los Angeles, but had moved in May 1945 to Paris, Texas, where Alline’s family lived and where William Cole owned a dairy farm. In August of that year he had sold the farm and was preparing to move back to California. Patterson hitched a ride with the couple, most likely to see the waitress with whom he had been corresponding.

On the way the trio stopped in Amarillo, Texas, to visit Aline and Ted’s older sister. There William Cole had a new engine fitted in the DeSoto, paying $305.97 in cash for the work. Cole was in the habit of carrying large sums of cash and it was known that he had left Texas with some $7000 (that would be around $126,000 today). One of those who knew this was, it seems, Ted Patterson.

At 1pm on September 1, 1945, the trio left Amarillo, Cole keeping to the instruction of his mechanic to drive not more than 35mph for the first 300 miles and then to keep to under 45mph for the next 300 because of the new motor. With them went their mongrel dog; both the Coles adored the dog and spoiled it – during their stay in Amarillo the dog had refused to eat anything by cooked hamburgers.

At 9.50am on Sunday September 2, 1945, the DeSoto passed through the Agricultural Checking Station on Route 66 in Holbrook, Arizona with William Cole driving, Patterson beside him and Aline and the dog in the rear seat. But after that there was little trace of them.

The police considered the prospect that they had picked up a hitchhiker who had then killed all three of them (a 22-year-old called John Hanson was briefly questioned) but Sheriff Porter was soon convinced that Patterson was responsible for the death of his sister, and possibly for that of his brother-in-law. He and his deputies spent days slowly driving along Highway 66, looking for oil and also for a peculiar type of dark-coloured sand known as ‘Job’s Tears’ which had been thrown on the floor of the DeSoto to absorb Alline’s blood.

Sheriff Porter then worked out that the DeSoto had covered some 303 miles since Holbrook and surmised that would be 150 to a point and back, making it likely the murder had taken place in California. His men searched Route 66 from the point where the DeSoto was abandoned, westwards into California, only returning to Kingman when darkness fell.

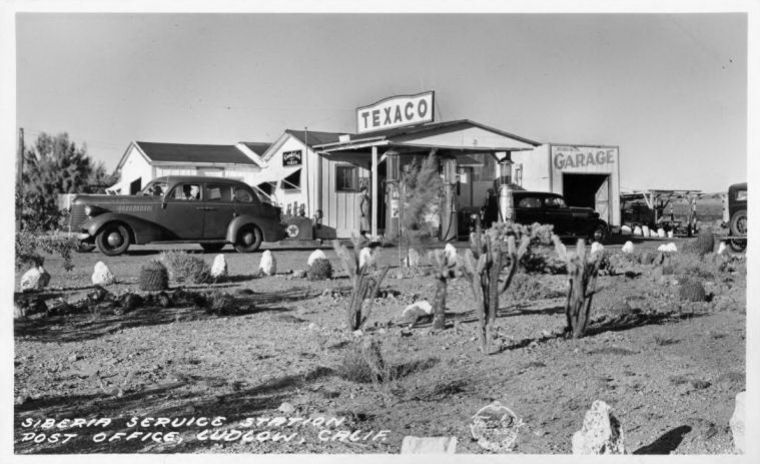

It was not the sheriff’s deputies who found William Cole’s body, but some tourists who, on September 29, had stopped at the side of the highway near Siberia for the night. They let their dog out of their car, only for Fido to return a few minutes later with a man’s legbone. The clothing found on the skeleton matched the last known description of William Cole and, proving Sheriff Cole’s distance theory, he was found 140 miles from where his wife had been buried (and some 15 miles from where the deputies had had to curtail their search).

Near the body was a large bloodstained rock which had been used to crush Cole’s skull. Also found were matches with a green head and red tip, identical to those found in the DeSoto. Just $6.48 was found on William Cole. All that was missing now was Ted Patterson – and the $7000.

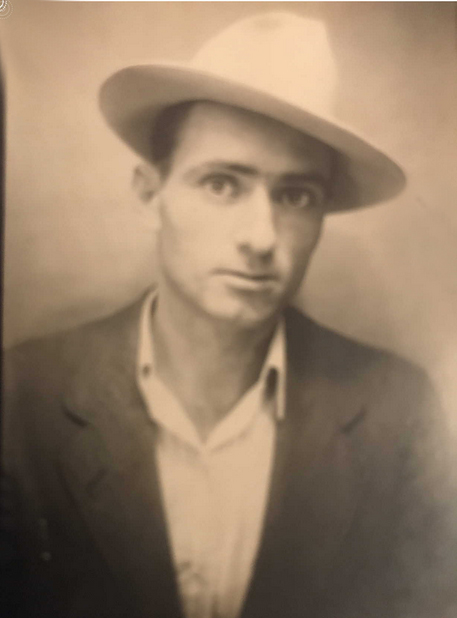

Ted Patterson was two years older than his sister and, like her, had grown up on a farm in Paris, Texas. At the age of 21 he had joined the Marines but, by 1940, he was back in Paris Texas, working as a machine operator and married to Laura Jones who he had wed in February 1938. The union would produce two children but end in divorce – papers found in the car showed that Emmett was desperately short of money, now an itinerant taxi driver, and had not been providing for his kids.

On October 13, 1945, came the news that Patterson had been arrested by a Union Pacific railroad officer near Kelso, California, after having been found sleeping in a sand bed near the tracks. Kelso is only a few miles from Siberia, but around 120 miles from where the DeSoto had been abandoned. Why would he have retraced his steps to where he killed William Cole? The simple answer is, he didn’t. The man in the sand bed wasn’t Emmett Edwin Patterson.

Ted Patterson might well have gone undiscovered had it not been for his temper and his weaknesses for waitresses. It turned out that he had travelled to Hot Springs, Arkansas (how is unknown) where he had taken a job on a dairy farm under the name of Tom Morton. While delivering milk to a café in Hot Springs, he met a waitress and took her to a party on New Year’s Eve, 1945. They both got drunk, had a row, Patterson hit the girl and broke her jaw. She had him arrested the following day, but his luck held. He wasn’t fingerprinted and so his real identity wasn’t revealed. It was only in February 1946 that a sharp-eyed Hot Springs policemen looked through the wanted circulars and spotted the photo of a man wanted by the Sheriffs of Mohave and San Bernadino counties. On March 1, 1946, Emmett Patterson was arrested and taken to California to be tried.

When his trial began on July 16, 1946, in San Bernadino, Patterson had a story. He claimed that the trio had stopped by the side of the road in Siberia (although it was known by relatives that the Coles were afraid of sleeping by the roadside). He had been asleep when he had heard the dog barking and woke to find Cole, gun in hand, beating his wife. Despite claiming he was scared of his brother-in-law, Patterson leapt to his sister’s defence, picking up a rock and beating Cole to death with it, as well as throttling him. However, the trial testimony brought out the fact that Cole was a small man, 20 years older than the ex-Marine, and had suffered from tuberculosis. Moreover, relatives said that Cole not only didn’t like Patterson, but was indeed scared of him.

Patterson stuck to his story, insisting that he then had put his sister in Cole’s DeSoto, planning to take her to hospital in Kingman but, just eight miles later, had found she was dead. So, letting the dog off its leash (the dog was never seen again) he said, he intended to take Alline back home to Paris, Texas, until he realised that having a dead body in the car would invite awkward questions at the Kingman inspection station. Instead, he stopped at Ed’s Camp between Oatman and Kingman, being careful to park the car a hundred yards east of the entrance and spent the day there. After dark he headed east but then stopped at 17 Mile Wash where he buried Alline, saying he had given her a “Christian burial”.

Perhaps it was this last element that helped him escape the death penalty for which the prosecution had asked. But the jury took just minutes to declare him guilty of two counts of first-degree murder and recommend life imprisonment.

Emmett Edwin Patterson served 17 years in San Quentin. He was paroled in April 1963 to Humboldt County where he died in September 1988. Alline never got back to Paris, Texas; she and her husband are buried in the Mountain View Cemetery in Kingman where, as a last insult, the gravestone lists the wrong year of birth.