This image is what brought me to Route 66

The old Twin Arrows Trading Post, east of Flagstaff, is a place for which I hold a particular affection. It wasn’t the first Route 66 landmark that I visited, but it was the one that seemed the most familiar. I’d seen the pair of striking red and yellow 20-foot arrows in countless photos and on the front of Route 66 guides. They were a Mother Road icon.

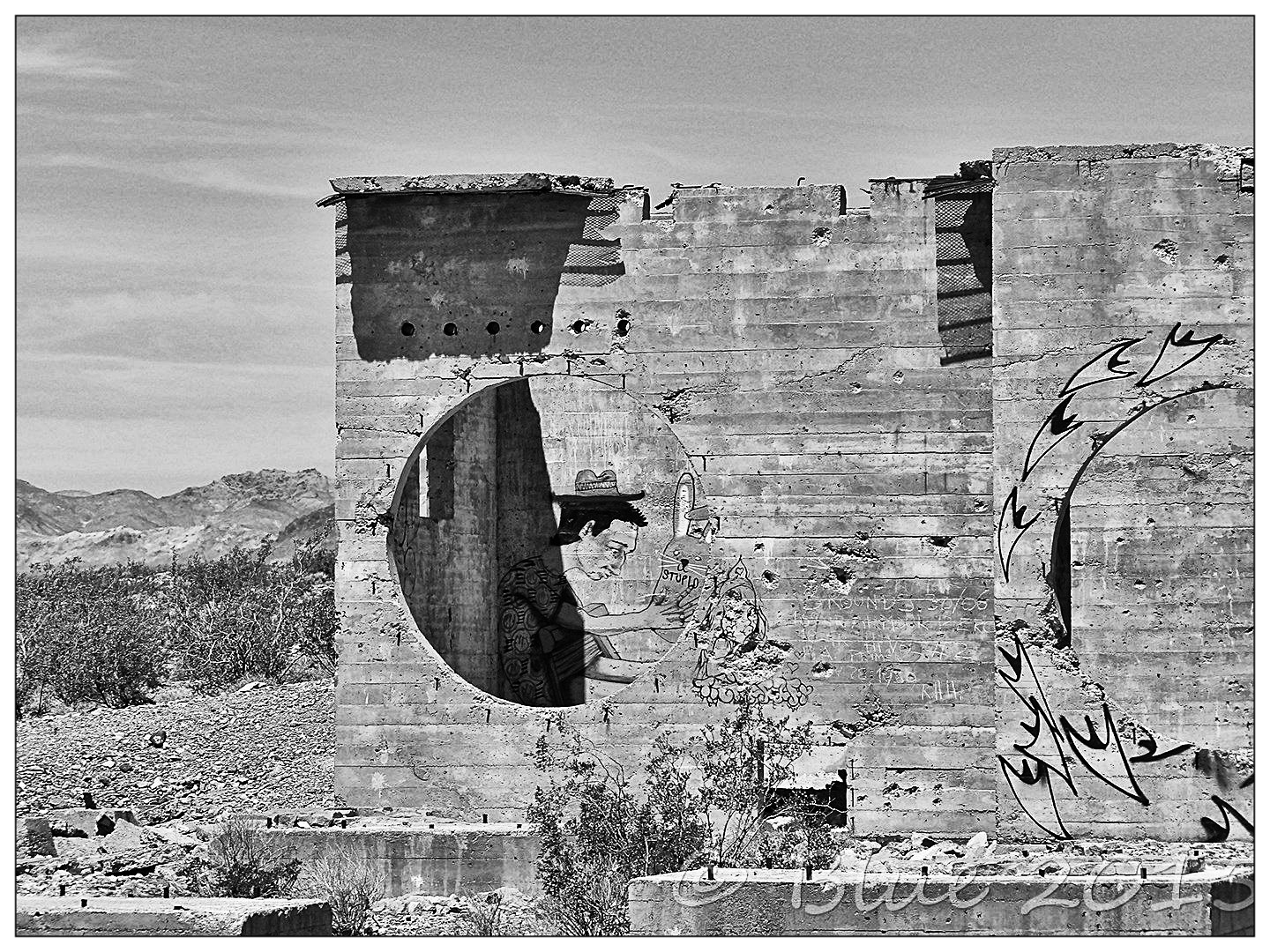

The exterior was repainted a few years ago, but that just provided a blank canvas for rattle cans

And then, one day in 2006, I rolled up at Twin Arrows. I was prepared for the fact that the trading post and café would be derelict, but not the arrows. Not those wonderful, iconic symbols of Route 66. But there they were, barely more than two telegraph poles slanted into the ground, feathers missing, unloved and abandoned. For me, it was as if someone had put in all the windows of Buckingham Palace and no-one had noticed. Or cared.

Three years later, the arrows were restored to their former glory by volunteers and a group from the Hopi tribe and brought back a glimpse of the forty or so years in which this was a popular stop for travellers through Arizona. The trading post started life in around 1950 as the Canyon Padre Trading Post, established by FR ‘Ted’ and Jewel Griffiths. However, while working outside the post, Ted was hit by a passing

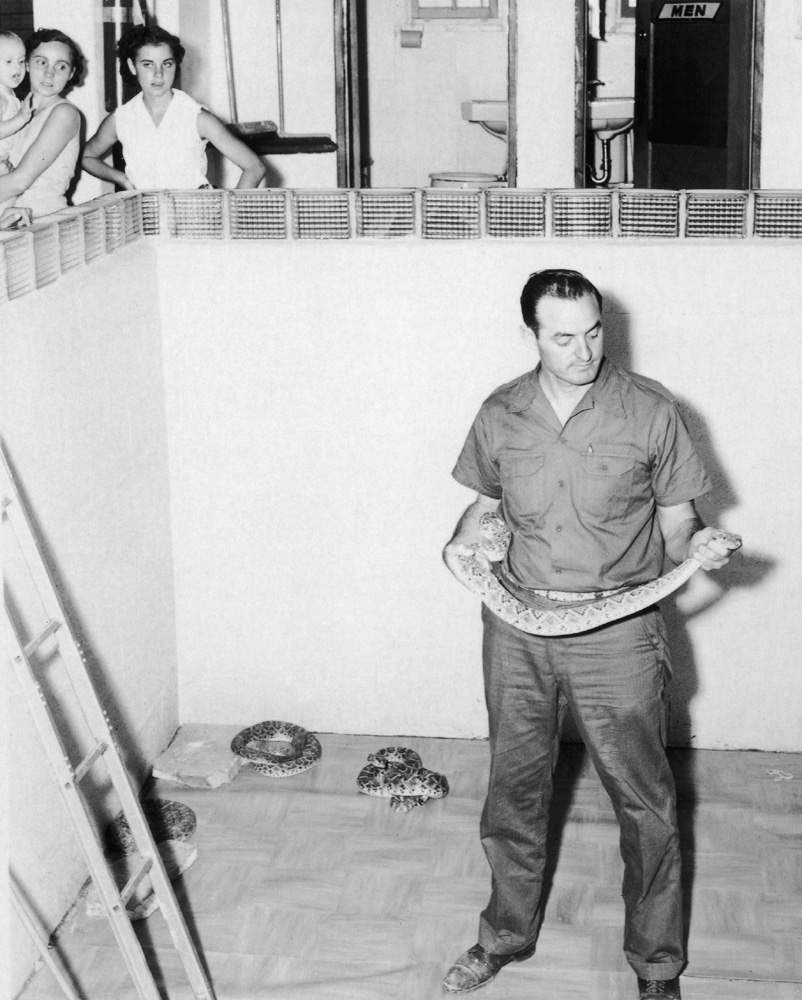

WH ‘Trox’ and Jean Troxell [Photo copyright of the Troxell Family]

motorist and his injuries meant he had to sell the business. On 15

th April 1955, ownership passed to William Harland ‘Trox’ Troxell and his wife Margaret Jean (who was known by her middle name).

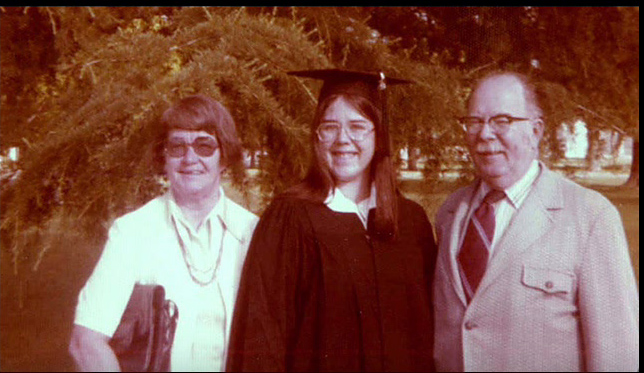

Trox and Jean were already established in the area, running a photographic studio in Flagstaff. While serving in the Navy in the South Seas, Trox was appointed ship’s photographer on the Rocky Mount. He decided to capitalise on his skills in this area and, on 8th March 1947, he and Jean opened their shop in downtown Flagstaff. When they purchased the trading post, responsibility for running the remote business fell on the shoulders of Jean and her parents, Edna and Levi ‘Max’ Maxwell. The Maxwells lived at the post while Jean commuted each day. For almost thirty years, she drove the 22 miles along the two-lane Route 66 from Flagstaff to Twin Arrows, seven days a week.

The infamous anatomically correct statues – alas, no photo seems to exist to prove this!

The Troxells changed the name to Twin Arrows, a rejoinder at the nearby Two Guns, and installed the famous arrows, along with two giant statues in loin clothes (apparently, anatomically correct underneath, as many travellers checked!) and a coin-operated telescope which offered views of the San Francisco Peaks. The store stocked a vast range of souvenirs and Indian goods, while gas was pumped outside. There was already a Valentine’s diner – one of the readymade buildings that was delivered, ready to roll, complete with furnishings – on the site, but the Troxells decided to lease this out.

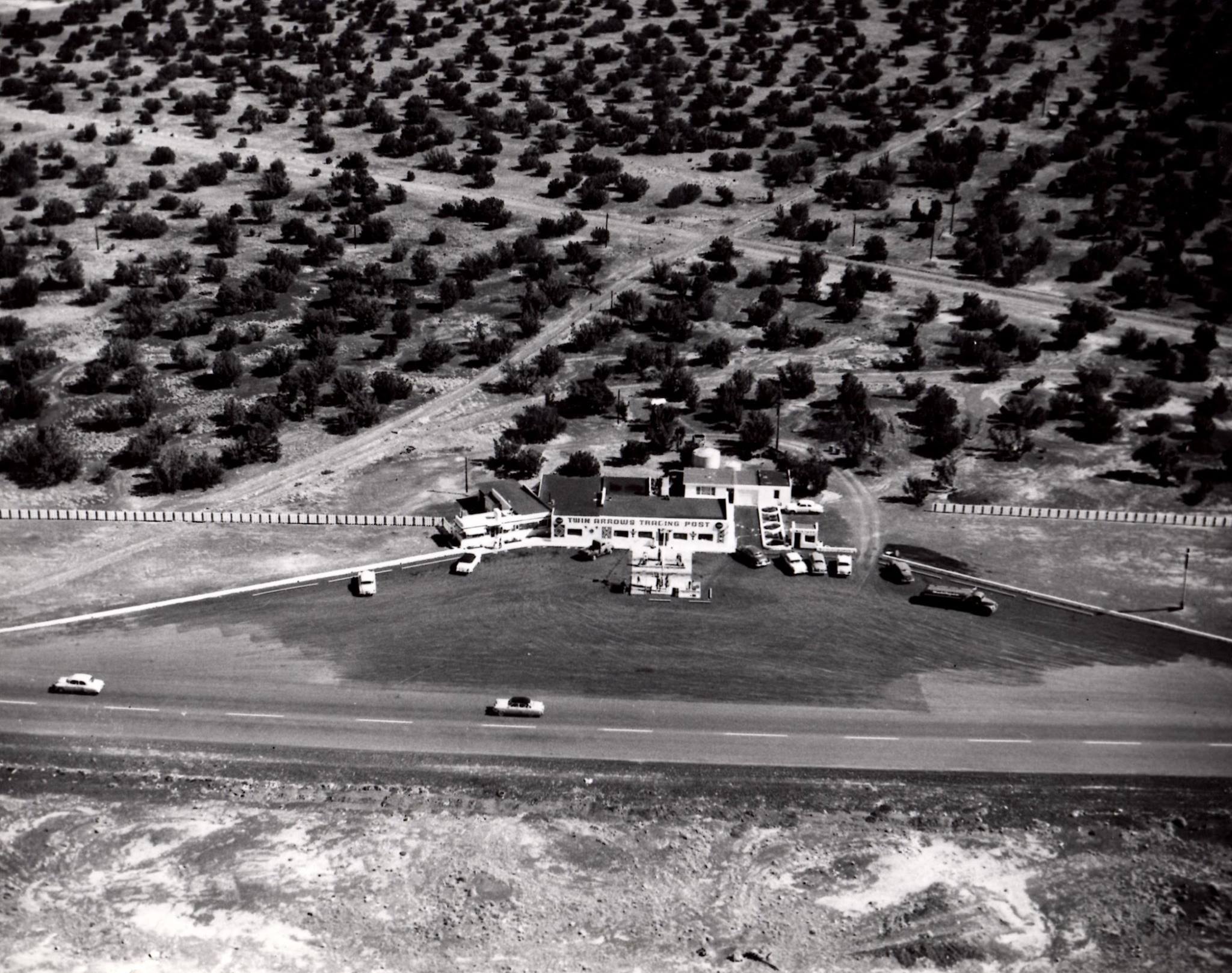

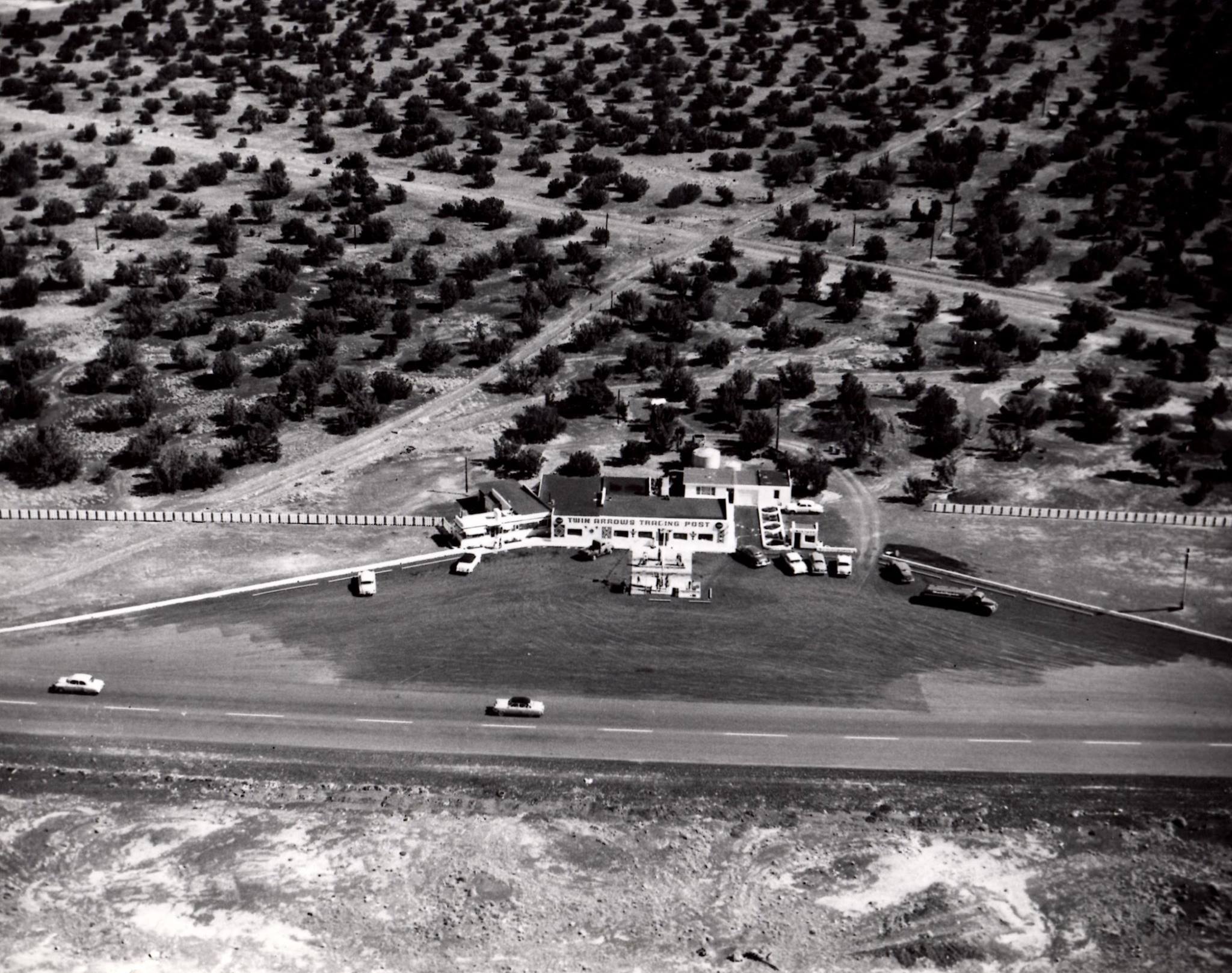

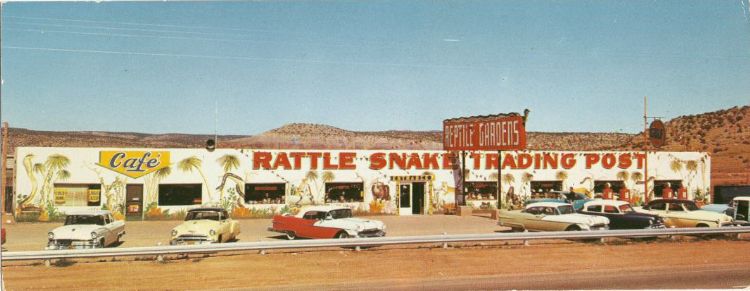

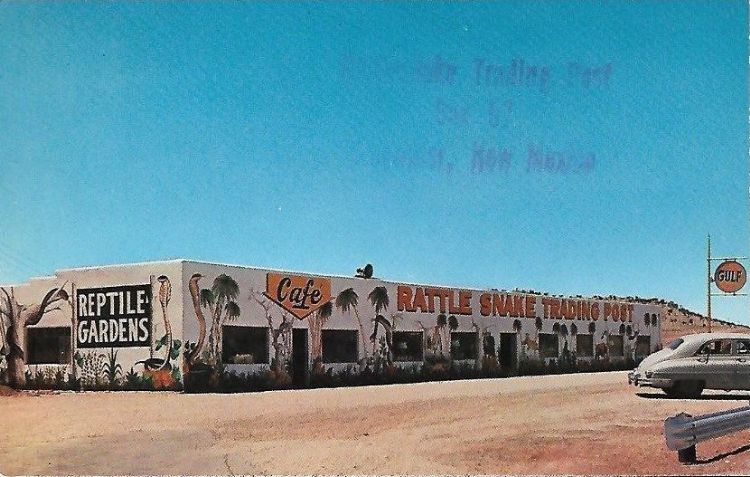

The Twin Arrows Trading Post in 1955 when the Troxells bought it

The store was run as a family business, with all three children working at the shop and gas station, something which, daughter April says, gave them all the chance to save for their college education. The whole family knew about hard work; as well as running and expanding the original photographic business, Trox managed to record a three-minute radio programme every day for 30 years, expounding on political commerce, travel, economic matters and what he called just ‘plain horsesense’. He was also a Scout leader for a quarter of a century, a respected member of the local business community and photographed the local area and events, including the building of the Glen Canyon Dam, while both he and Jean were deeply involved in the Happy Farm Orphanage in Sonoita, Mexico.

The well-stocked interior of the Twin Arrows Trading Post

Being in a remote spot, Twin Arrows saw its share of drama, and not all of it involved traffic accidents, although there were a number of accidents on the old two-lane road, some fatal. In 1952, 54-year-old Virginia McNabb was killed outside the post when she rolled her ’59 green Plymouth. In 1960, 19-year-old Robert Stone was jailed for a year and a day in the state prison in Florence for robbing the coin-operated telescope of $68 (either that was one expensive telescope or it wasn’t emptied very often!) If that seems a harsh sentence, then it may be because young Stone had something of a record. In the few months since he’d moved from North Carolina to Winslow he had been arrested for burglary, liquor offences and was a passenger in a car in which Carol Wickham, the teenage daughter of a Winslow councilman, had been killed.

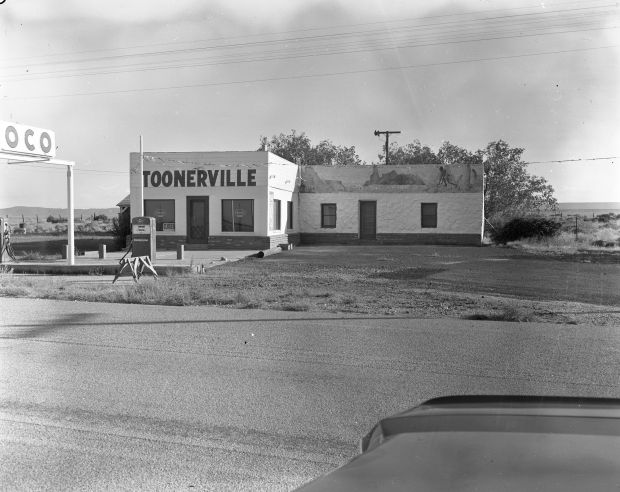

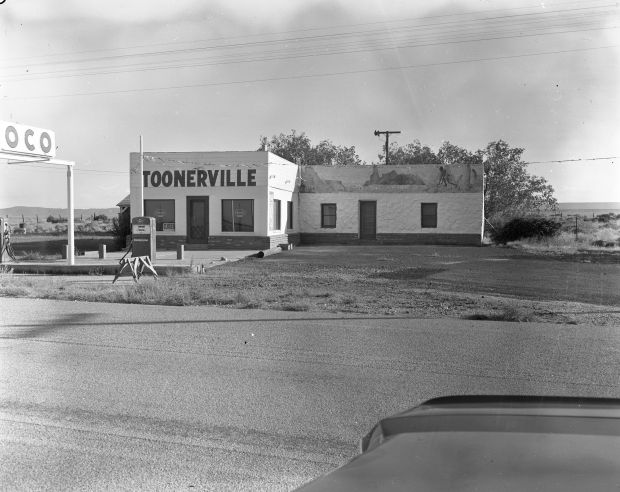

Toonerville, where Slick McAlister was shot to death. It’s still a cold case.

In 1959, Ary J Best, a 66-year-old tourist who had made his last stop at Twin Arrows, was stabbed to death and his body dumped east of the trading post; a couple was later arrested in Pasadena after abandoning the victim’s car and charged with his murder (Patrick MacGee went to the gas chamber for the crime in 1963, his girlfriend, Millie Fain, was sentenced to 14-20 years in prison). But crime came far closer to home on 30th August 1971. Shortly after a car had stopped for gas at Twin Arrows, the trading post received a panicked phone call from Mrs Pearl McAlister at the Toonerville post a mile away. Those motorists had also stopped there, and while she was cooking them hamburgers, they had shot her and her husband and ransacked the place. Merrett ‘Slick’ McAlister died at the scene. The murder has never been solved.

This may be the reason why, for the next few years, the Twin Arrows diner found it difficult to get staff, advertising regularly in the local paper, raising the hourly wage offered from $1.25 to $1.60 over the months.

The diner and the trading post in the 1970s

After Max retired and their son Jim went into the Navy, the Troxells hired a couple to manage the trading post but when they finally retired, Trox and Jean found it difficult to find good help. The trading post stood on state-owned land and, despite countless attempts by the Troxells, the state of Arizona refused to sell them the 10 acres. In 1971, Interstate 40 opened on this section, although Twin Arrows fared better than other places. The initial scheme would have seen it bypassed by an overpass, but, thanks to a Troxell family member who was a civil engineer and submitted an alternative – and cheaper – design which was accepted, Twin Arrows was given its own exit. However, trade still dropped off.

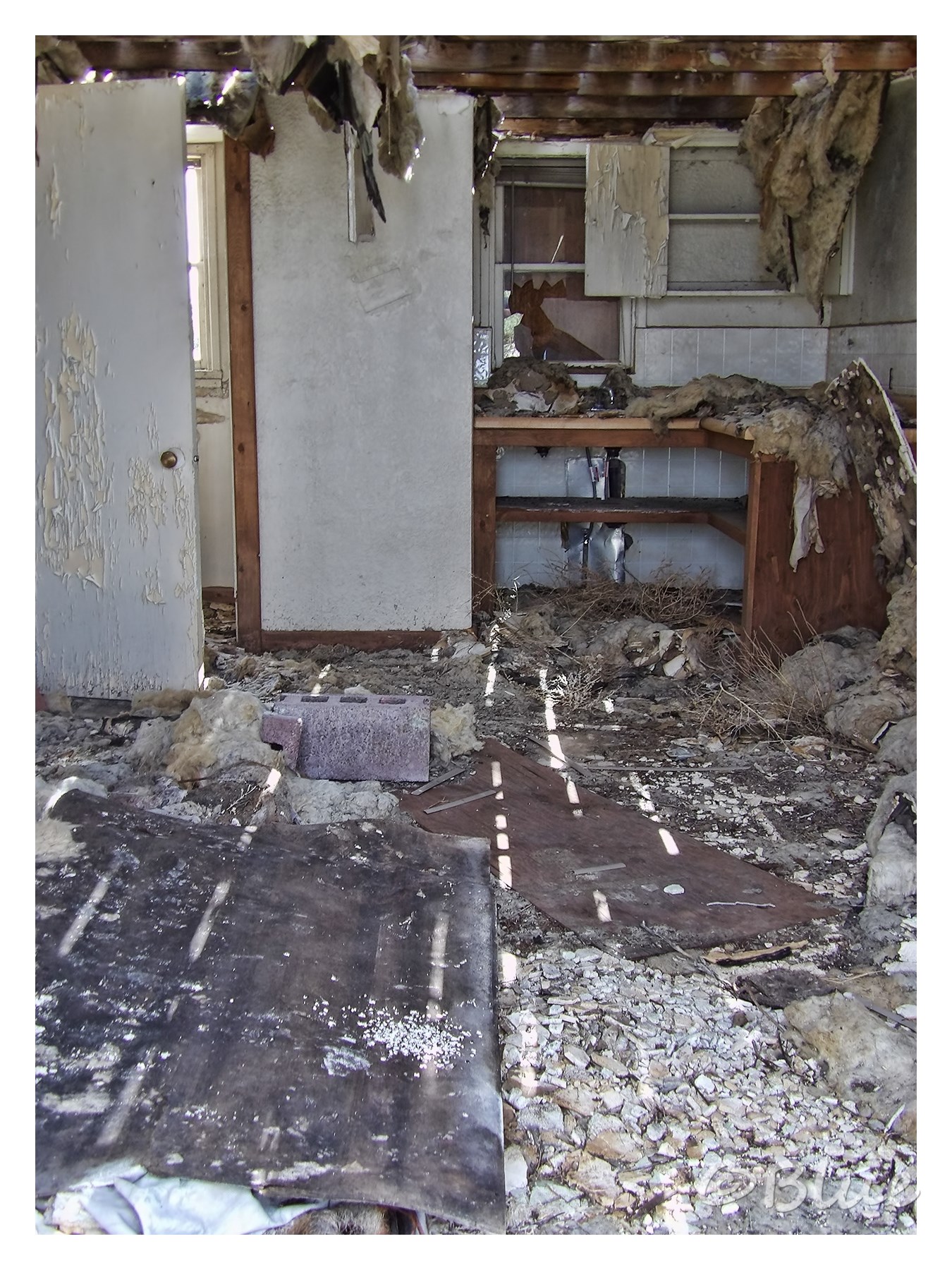

Still distinctly a Valentine diner, the 65-year-old manufactured building has held up surprising well against the weather and vandalism, but is probably beyond saving

In 1995, Spencer and Virginia Riedel took over the trading post and attempted to revive it. Virginia had wanted to restore the Valentines diner in 1950s style but it was economically unviable to bring it up to county code. The Twin Arrows Trading Post closed for the last time in 1998. It was finally the end for the famous Route 66 stop. The trading post is now owned by the Hopi and, despite plans to restore it, it continues to fall into decay and ruin. The arrows still stand, but even they, like the glory of the Twin Arrows Trading Post, are now fading away.

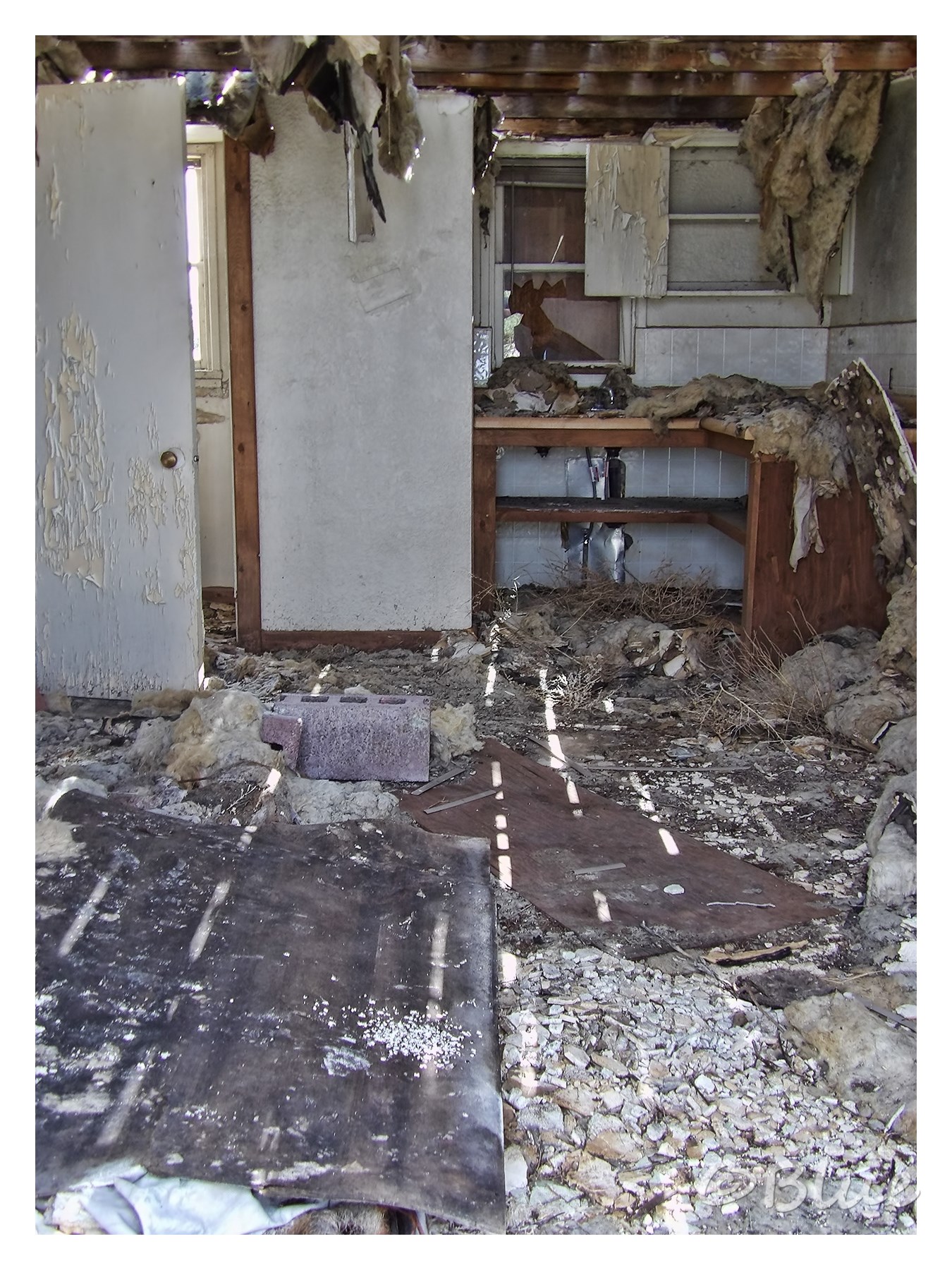

The interior of the Valentine diner

The rear of the trading post where there was living accommodation

The decaying interior of the trading post

The pumps in the background would, I assume, have been for trucks rather than cars

The CAFE sign is untouched by graffiti, possibly because they couldn’t reach…

UPDATE: Sadly after writing this article, the grafitti idiots finally got to the CAFE sign as well as painting over part of the TWIN ARROWS TRADING POST signage. In the last two years, the place has become increasingly vandalized and much of the interior cladding has been ripped away. Unfortunately, I predict that one day I will pass by here and it will have been burned to the ground.

On the long stretch of I-40 that crosses Arizona, a clay-coloured dome breaks up the monotony of the landscape. To the south of the interstate, on what was old Route 66, sits the remains of the Meteor City Trading Post.

On the long stretch of I-40 that crosses Arizona, a clay-coloured dome breaks up the monotony of the landscape. To the south of the interstate, on what was old Route 66, sits the remains of the Meteor City Trading Post.

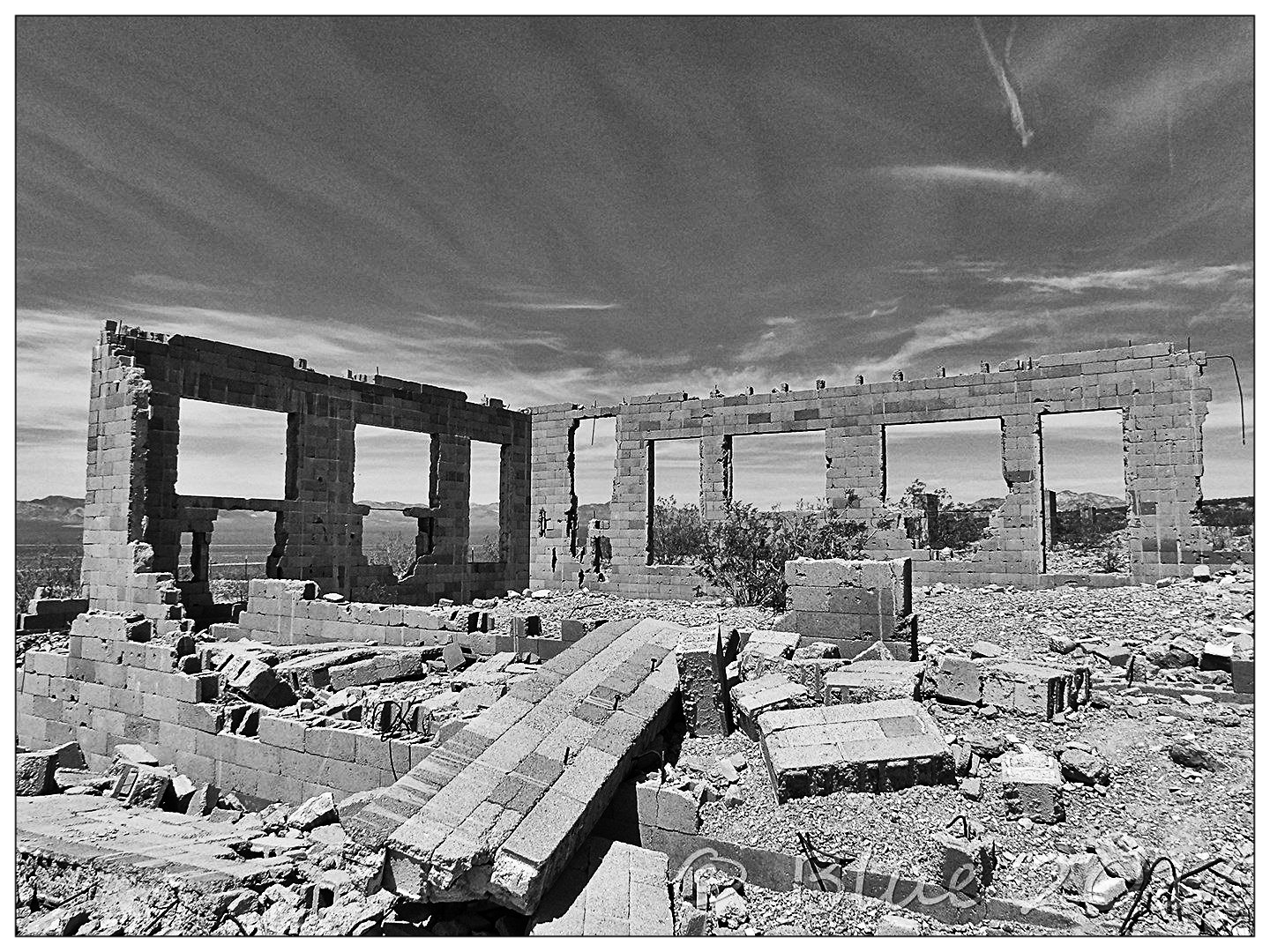

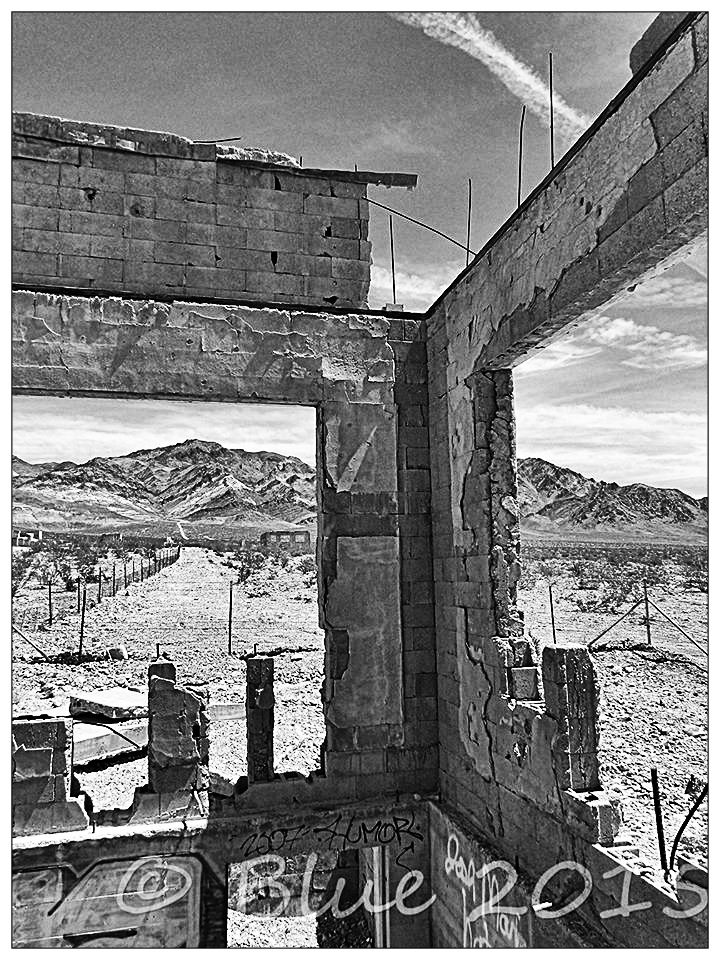

Although officially known as the Carrara Portland Cement Company Plant, it was usually referred to as the Elizalde works after Angel M Elizalde, a major investor in the plant and director of the company. At the time, it was intended to be one of the most advanced plants of its kind in the USA with houses for the workers. It would produce commercial grey cement and also a fancy high quality cement made from the crushed marble and clay from the nearby Carrara quarry.

Although officially known as the Carrara Portland Cement Company Plant, it was usually referred to as the Elizalde works after Angel M Elizalde, a major investor in the plant and director of the company. At the time, it was intended to be one of the most advanced plants of its kind in the USA with houses for the workers. It would produce commercial grey cement and also a fancy high quality cement made from the crushed marble and clay from the nearby Carrara quarry. However, the factory never went into operation. The popular notion is that it provided to be too costly and logistically difficult to move the cement. Whether that’s true or not, just a month before production was due to start in July 1941, a fire completely destroyed the machine shop, storehouse, blacksmith shop and an office. A few weeks later, the Carrara Portland Cement Company at Carrara closed down, apparently unable to find parts to replace those lost in the fire.

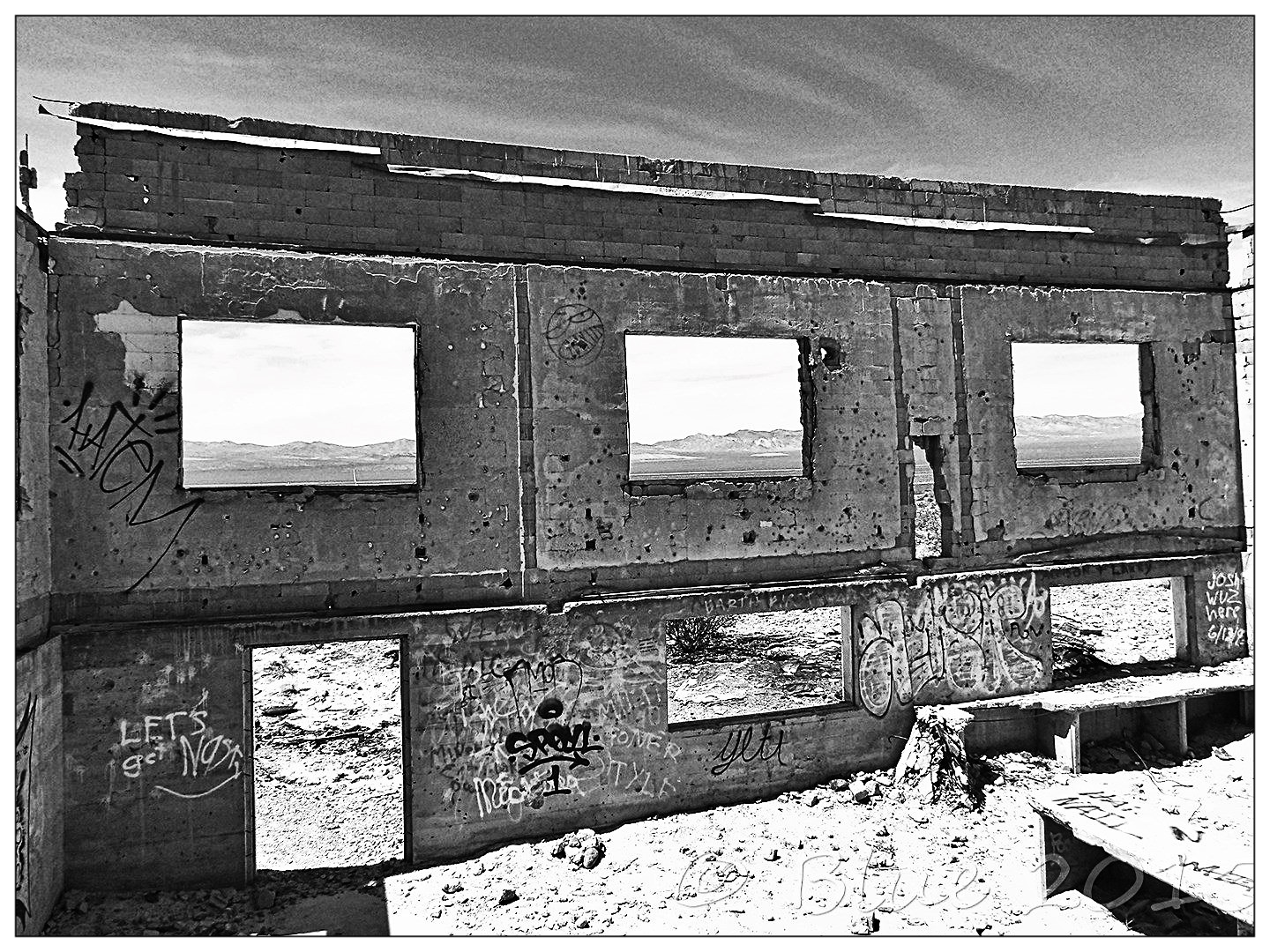

However, the factory never went into operation. The popular notion is that it provided to be too costly and logistically difficult to move the cement. Whether that’s true or not, just a month before production was due to start in July 1941, a fire completely destroyed the machine shop, storehouse, blacksmith shop and an office. A few weeks later, the Carrara Portland Cement Company at Carrara closed down, apparently unable to find parts to replace those lost in the fire. The company, however, announced its intention to continue, and then Pearl Harbor happened. The advent of fuel rationing in the following spring made it impossible for the company to run its machinery and transport its goods, even if it had been able to get the plant back up and running, which, without sufficient diesel was impossible. It was abandoned, although some of the machinery remained for several years. Today, the only visitors are those wielding aerosol cans or those who’ve glanced up from Highway 95 and been curious enough to drive the deteriorating track.

The company, however, announced its intention to continue, and then Pearl Harbor happened. The advent of fuel rationing in the following spring made it impossible for the company to run its machinery and transport its goods, even if it had been able to get the plant back up and running, which, without sufficient diesel was impossible. It was abandoned, although some of the machinery remained for several years. Today, the only visitors are those wielding aerosol cans or those who’ve glanced up from Highway 95 and been curious enough to drive the deteriorating track.

Clyde was two years old himself when his parents, Victor and Lydia, moved to Palmetto from Santa Rosa, California, no doubt hopeful of making that big strike and never dreaming they would lose both their sons so tragically. The marker only mentions Clyde, and people have often assumed that Kenneth was buried with him. However the little boy lies alone, his younger brother having died and been buried in Silver Peak, another town to the north west. The Blair News reported that Mrs Hart had ‘been quite ill for several days prior to starting for California, her illness being aggravated by the mental anguish of the loss of the children in so short a time.’

Clyde was two years old himself when his parents, Victor and Lydia, moved to Palmetto from Santa Rosa, California, no doubt hopeful of making that big strike and never dreaming they would lose both their sons so tragically. The marker only mentions Clyde, and people have often assumed that Kenneth was buried with him. However the little boy lies alone, his younger brother having died and been buried in Silver Peak, another town to the north west. The Blair News reported that Mrs Hart had ‘been quite ill for several days prior to starting for California, her illness being aggravated by the mental anguish of the loss of the children in so short a time.’ After burying their children, the Harts continued back to California; Lydia gave birth to a son, Alan, almost exactly a year to the day after Clyde’s death, and a daughter, Evelyn, in 1910. Both Lydia and Victor lived into old age, Victor dying in 1958 at the age of 80 and Lydia living until she was 97 and they are buried beside each other in the Oddfellows Cemetery in Sacramento. Having lost two children so young, it must have been a consolation that their son and daughter lived long and full lives. Alan died in 1994 and Evelyn just nine years ago aged 96. Did the family ever come back to Palmetto to visit the grave or was it too painful a part of their life?

After burying their children, the Harts continued back to California; Lydia gave birth to a son, Alan, almost exactly a year to the day after Clyde’s death, and a daughter, Evelyn, in 1910. Both Lydia and Victor lived into old age, Victor dying in 1958 at the age of 80 and Lydia living until she was 97 and they are buried beside each other in the Oddfellows Cemetery in Sacramento. Having lost two children so young, it must have been a consolation that their son and daughter lived long and full lives. Alan died in 1994 and Evelyn just nine years ago aged 96. Did the family ever come back to Palmetto to visit the grave or was it too painful a part of their life? I thought at first how odd it was that there are no other graves in the area, but because Palmetto existed for such a short time – the silver that was struck lasted barely a year – it could be that the little Hart boys were the only people to die out in this lonely place. But the toys and paraphernalia on the grave (I left a toy car) show that they are not forgotten.

I thought at first how odd it was that there are no other graves in the area, but because Palmetto existed for such a short time – the silver that was struck lasted barely a year – it could be that the little Hart boys were the only people to die out in this lonely place. But the toys and paraphernalia on the grave (I left a toy car) show that they are not forgotten.